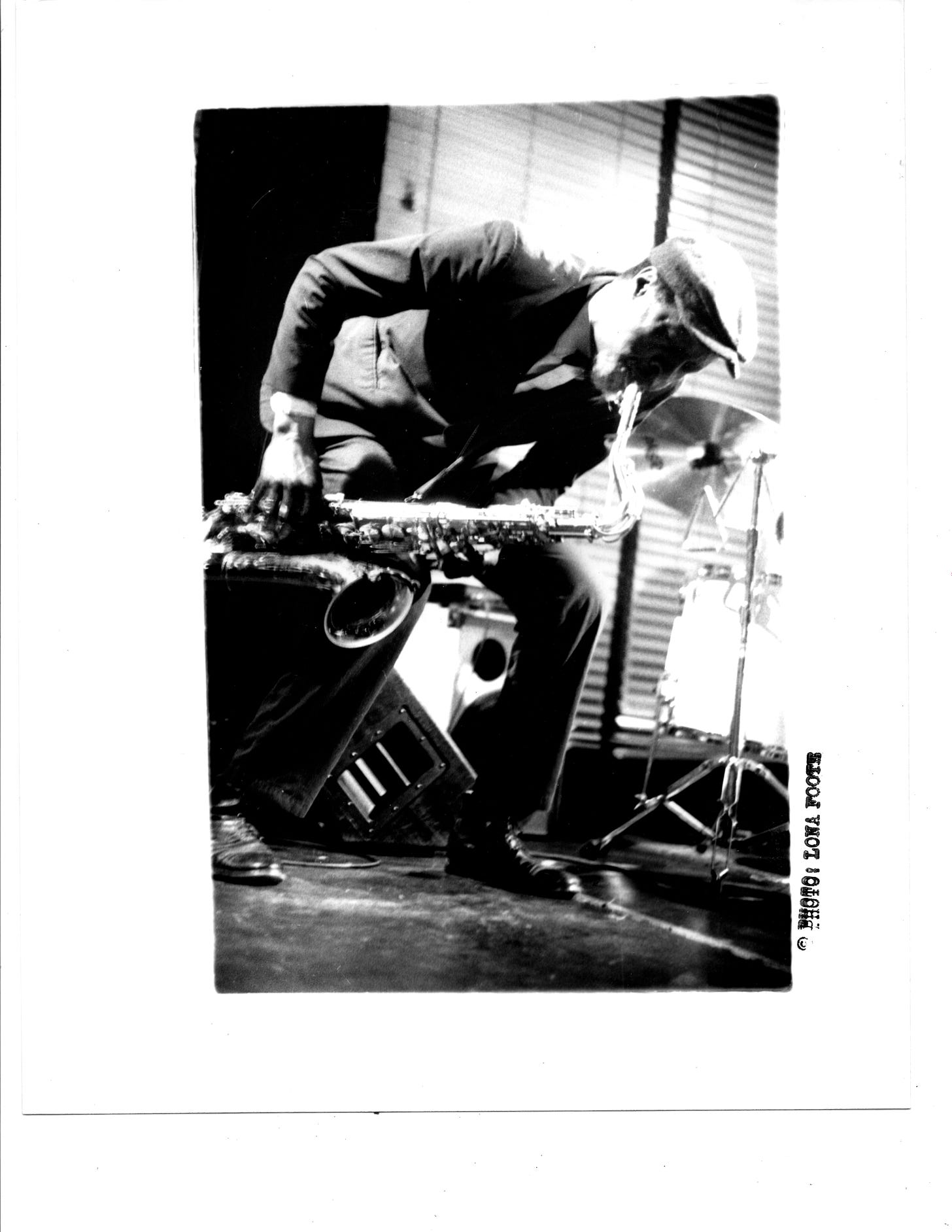

This was Charles Gayle, 30 years back

My feature for The Wire, March 1994 on the powerful, original, now deceased tenor saxophonist of NYC's Lower East Side, far from commercial jazz.

Regard for “free jazz” improved considerably in the course of the 30 years since this was first published — or I was exaggerating for effect in my reporting back then (I think not). International opportunities, federal and state arts grants helped sustain some of New York's more marginalized free jazz musicians in the early ‘90s, helped enable tours, spread their ideas and sounds, grew their audiences. Increased jazz world embrace of the late career breakthroughs of John Coltrane and Sun Ra’s Arkestra, the ongoing iconoclasm of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor et al — the grandly daring to outright outrageous, impolite to impervious, staunchly political and/or spiritually transcendent aims of Ayler, Shepp, Sanders, Mingus, Cherry, Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda, Abbey Lincoln/Aminata Moseka and Max Roach — were further valorized. The music’s immediacy and urgency proved enduring.

In 1998 Gayle’s colleague David S. Ware' was signed by Branford Marsalis to a multi-album deal with Columbia Records. His quartet comprised drummer Susie Ibarra and Gayle’s frequent collaborators pianist Shipp and bassist Parker. The latter is among “free jazz” musicians who’ve over the years won greatest acceptance and support, named a Doris Duke Performing Artist in 2013, which led to his co-founding with Patricia Nicholson Parker, his wife, the annual Vision Fest for this music. Gayle was honored with the Vision Festival’s Lifetime Achievement recognition in 2014; he had continued to perform, sometimes as Street, a mime, and record, including two collaborations with vocalist Henry Rollins, last releasing music in 2019.

Contrary to how it seemed in the ‘90s, and although its still not widely hear or richly funded, the basics of a “free” jazz — in which players are themselves, interacting with as much or as little structure, as spontaneously or pre-set as they agree to, upsetting traditions or drawing on them at will — is well-established. Kamasi Washington can be considered today’s most prominent heir of the sound — well-received by young audiences, directly tied to the 50-year-long dominant music from Black American culture (hence, the world), hip-hop.

This should be no surprise. After all, flagrantly unruly, unabashedly discordant polyphonic collective improvisation is jazz bedrock, a vein in rippling through earliest recordings by the progenitors. It’s a 100 years since Oliver/Armstrong’s “Dippermouth Blues,” Sidney Bechet’s “Wild Cat Blues” and Jelly Roll’s “Big Fat Ham,” all extolling freedom in/of music, flaunting conventions for fun and whatever profit they could squeeze from it. Charles Gayle, who lived to age 84, may have gotten modest benefit from all this — but he was free.

Thank you for posting this, Howard. This is invaluable reportage!