Roy Haynes' long, unvarnished interview, 1996

"You've got to make it exciting," the great drummer said on the phone, setting up our interview. "My whole life in music--from the beginning to right now--it's been so exciting, man!"

I was honored to have Roy Haynes come to my Greenwich Village office for a DownBeat interview in 1996. Arriving around noon, he was dapper as always — I daresay Roy Haynes was the epitome of “jazzy” — and my place the usual mess, but with large windows on the sky over Sullivan Street, to gaze through while talking.

I’d first become aware of Haynes seeing saxophonist Stan Getz’s quartet with him, vibist Gary Burton and bassist Steve Swallow at a free show in the parking lot of a suburban Marshall Fields’ store, around the time of this video.

Back then I liked Haynes on Gary Burton’s Duster, got into his own quartet album Out of the Afternoon (with pre-Rahsaan Roland Kirk on multiple horns, often at once; pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Henry Grimes) and was awed by Haynes how h pianist Chick Corea and bassist Miroslav Vitous flowed together through Now He Sings, Now He Sobs now a well established classic, I loved it on release in 1968. For decades, listening to diverse records, I’d hear a spark and wonder — “Who’s that?” Roy Haynes, of course. Here he is in transcript, very lightly edited for clarity.

He’d recently completed a tour and recording with Chick Corea and all-stars performing a tribute to Bud Powell — with whom he’d played in the 1940s. He refers to that and much else across 50 years of jazz history below. We sat down on chairs close to each other, I stuck out a hand-microphone for a broadcast-worthy pre-digital tape recorder. He said I should have had a glass of cognac and one of water, ready at his right hand. I hurriedly filled and brought us glasses of water.

RH: Yeah. I'm with you. You gonna hold that? Oh, man, that's a drag. I don't like shit looking at me like that [chuckles].

HM: You'll forget about it later.

RH: I should have brought my shades.

HM: This morning I got this tape of an upcoming Stephane Grappelli - Roy Haynes record [Flamingo, with Michel Petruccciani, piano, and George Mraz, bass].

RH: Really!

HM: How'd you like it?

RH: I haven't heard it. I don't remember. I remember there were moments on it. I like him [Grappelli], anyhow. Because I was into the Hot Club of France, you know. I used to hear this stuff on the radio when I was a kid. Yeah. My agent in France — I have a French agent, Bernard, he's the one who got me with Disques Dreyfus [record label], in fact. And he's the one who's saying, “Well, Haynes, since you played with almost everybody, you might as well play with Stephane Grappelli.” So we went in the studio. And he was a gas. The first time we ever played together. He was asking for my number — he had his people with him, you know, took my number just in case [he wanted to get in touch for another session]. So, you never know, man. But you like the record or what? There must be some moments on it.

HM: It's clean -- you give it more --

RH: More “up”?

HM: Jet-stream.

RH: Oh, yeah? That's cool.

HM: I'm surprised you heard that stuff on the radio as a kid.

RH: As a kid. Man, I heard everything. I heard, Bing Crosby. Sure, Are you kidding? I heard all kinds of -- I used to listen to all the music. Wednesday night Glenn Miller used to come on in Boston, 10 o’clock, I think. I was into that. I heard a lot of Art Tatum as a youngster, all the singers, Basie's band, Duke's band. I had an older brother that had all of Duke's and Basie's and Billie Holiday's stuff -- he had all the records. So I heard all of them, then my ears were open to everything that was on the radio. Including Irish music.

You know, Boston was really Irish. We had Irish people who lived on the left. And a Jewish synagogue across the street. So we used to hear them, you know — the funerals that used to come out . . . I heard everything, man. This is is Roxbury, 1930s, '40s. It was like the UN during that period. It was a gas.

My own brother, he really never played professionally, but he went to the New England School of Music, and he studied trumpet, he studied theory. That was after he came out of the service. But in high school I think he was in the bugle and drum corps, so he had the drums sticks, and those were the first drum sticks I ever had — his.

There were four of us. He's not living now; there are three of us left. I have an older brother, fact we're celebrating his 75th birthday next week. He's Vin. then Mike, Michael is a baptist preacher, he's younger than me. Then my older brother Dougie, he's been gone quite a while. Mother and father from Barbados, they've been gone for a while. So the beat goes on.

HM: Was there Barbados music in your household, too?

RH: Not really. That would have been . . . In those days people come from other countries, it wasn't . . .

HM: They wanted to forget about this -- ?

RH: Not really, because this is all you heard. They wanted to talk about home all the time, my mother and father. They talked about it so much my younger brother ended up buying a couple of condominium's down there. So we were always down there, hanging out. I’ve still got a lot of relatives down there. Now I'm into the music more. You know, Calypso stuff. You notice on some of my records I did that, earlier. Yeah, I love it.

HM: Is there an active, present day music scene down there?

RH: They have their own, a jazz society and everything down there. For tourists, naturally.

HM: They treat you as a homeboy?

RH: A little bit. Not a 100 per cent. But I'm always there, I've got a lot of friends and relatives — in fact there was a place that opened, one of the younger buddies of mine down there opened a club some years ago called After Dark, it's still big, a disco and everything now, but when he opened he had one room and he called it The Royal of Haynes room. Yeah.

HM: Did you follow through high school music studies, like your brother?

RH: Yeah. I did it in junior high, mostly. I l was a drum major, calling the shots there. But after I got to high school — okay: We did the ninth grade which would have been the first year of high in those days, so when I went the second year, that school, I did't really like it that much, and I've talked about it in interviews, how I would drum on the desk with my hands, and the teacher sent me to the principal’s office and the principal told me not to come back until I had my parents or someone with me.

Then I went back, with my mother -- if I'd gone back with my father, my father would probably have kicked his butt -- but I went with my mother, and she always remembered that when the principal was talking about me to her, he didn't even look up and look at her, he has his head down, and he talked about me as if I was the worst child in the world, and he didn't even know me and I didn't know him, so I don't know where he was coming from. But I didn't go back to school much after that. I went to school with Lester Young, and Charlie Parker and Luis Russell, and all those people after that.

HM: You feel you missed anything by not having had more formal education?

RH: I don't think so. Not too tough, anyway. I don't speak much of the English language -- I don't speak it too good, so there's not much of a problem there. [Joking, laughs.]

HM: Do you read a lot? Consider yourself having a liberal education?

Roy Haynes, photo by Richard Conde (winner, JJA Photo of the Year 2018)

RH: To a bit. I used to read more years ago. As I got older my eyes got screwed up a little bit, but I'm up on things. I really learn a lot being a musician and traveling all around the wrold with all different type of people, learning about their life styles and everything, you know. I think you learn a lot that way. It's very educational, traveling. Really.

HM: The modern musicians, your generation on — not that earlier cats didn't do it --but the interactivity means you’re so open, so alert to details from different people [like Grappelli].

RH: Right. Exactly.

HM: And you don't have to read about it to get the reality.

RH: Exactly. You know what I mean. That's right. Like I hear, sometimes I watch maybe the Tonight Show, when Johnny Carson was on he'd talk about going to Japan or another country and how they treated him like a king, but see, we [jazz musicians] were getting that treatment way back in the days. The newspaper, the radio, they would come with their suits and ties on. There'd be a lot of them there, asking us questiona about our lives in our country. That way, it's been great.

I had a chance to go to Bangok years ago, hang out with the King down there, and the Queen as well, that's his wife. This music can take you up to Harlem or down to Brooklyn, I could be standing with somebody on the corner, chatting with them, or chatting with the president of our country. It's wide.

HM: And deep.

RH: Definitely.

HM: Whether you’re doing Stephane Grappelli, Chick Corea, older material -- I didn't listen to your work with Sarah Vaughan, I want to ask you about that, too -- but your drumming, it isn't about thinking about the past, it's about thinking about the next moment and this moment.

RH: Oh, s’il vous plais monsieur, oui -- great, this moment, yeah!

HM: I want to know how you make it fresh, to hit the ride cymbal like this [demonstrates hard] every gazillion-trillionth time. But first: You said when we did our Blindfold Test there was a parallel between playing for singers and playing for horn players?

RH: Maybe. I'm always into lyrics and melodies. so like with Sarah Vaughan I was enjoying it as well as playing and performing. Okay, I played with Billie Holiday a few times; when I joined Lester Young, which was October of 1947 — that same first week we played together started at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, that's where I joined him. I don't know if we had a night off, or we had closed -- we played at Town Hall, and I had to accompany Billie Holiday, for the first time. I was excited as hell, because I was always into Billie Holiday. Then I joined Sarah, as you know, and I played the summer of 1952 with Ella Fitzgerald and Hank Jones and Nelson Boyd, which was very memorable. And those things, these singers, plus others -- I recorded with Ray Charles, plus some blues people, yeah, “One Mint Julep” was one of the records he sings on I recorded with him. Let's see, what's the girl's name? — Etta Jones, “Don't Go To Strangers,” I'm on that.

Yeah, and with some other singers. Sometimes I forget. Somebody’ll telling me about this record I made with this singer, I’d forget her name, I forgotten all about it, in fact I wouldn’t have heard much about it since I made the record or much about the singer before, either.

Nobody ever told me to lay back with the singers, I know that's what you should do. In fact, during the period with Ella Fitzgerald, she was scatting, and singing fast, and there was a whole lot of stuff in there. It was like playing with Count Basie's band, playing with Ella. To play with Sarah was like to play with Bird. To play with Billie Holiday was like to play with Pres. I associate each one of them with another musician or artist they may have played with, or reminded me of.

[Roy Haynes and Sarah Vaughan: Please contact with photo credit]

HM: It doesn't sound like you’re negotiating a learning curve to your early stuff, it sounds like you've got your material already there.

RH: How early you speaking of?

HM: Early '50s, late '50s.

RH: Well, I’d come to New York, I was with a big band 1945 with Luis Russell. Started with them at the Savoy Ballroom, I had to check out charts and count bars, and I hand't even realized I was innovating then, because the guys told my brother when we came to Boston that I had changed the sound of the band, and it was just Luis Russell.

He believed in me. He had never heard me, somebody told him about me, a saxophone player by the name of Charlie Holmes, played alto, he was around Louis Armstrong and all those people -- I had played with him in Connecticut, and he told Luis Russell about me, Luis Russell sent me a special delivery letter, I was playing up in Massachusetts, Martha’s Vineyard, summer of 1945, For the whole summer. So I joined the band after Labor Day, and this guy believed in me. And it worked!

He believed in me just on what he heard about me, so I must have had something back then. I knew I could swing. I knew that.

HM: From the get go -- it doesn't sound you swing like Cozy Cole or Jo Jones, but you have your own --

RH: Oh yeah, I'm glad it sounds that way, but I like both of those guys, Jo Jones was a swinger -- in fact, we used to say he invented the high hat [the sound], you know.

HM What did you do different with Luis Russell that was innovative?

RH: I don't really know what I did that was different -- I just had certain things in my head I wanted to play, and I just played those things. I can't really say how different they were. It's an interesting thing when I read or maybe I hear about a musician will describe me. I was reading something [saxophonist] Ralph Moore was saying some time ago, and it really knocked me out to see how he described me. I'm learning about myself, you know. And to hear, maybe, Chick [Corea] describe or talk about me. Things that I’m doing subconsciously I'm aware of, but I'm not aware-of-aware-of them, you know?

Writers, sometimes -- you notice, I said musicians. With writers, sometimes it’s beautiful, sometimes they can bring out certain things that you’re really not aware of, and sometimes they get something else out of it, and they go a different way direction. You say, “Oh, really? Is that what they got out of it?” It's good to know what everyone is hearing, in the music that you're about, you know.

HM: What I hear is a semi-circle-like shell in front of you, your surfaces all laid out around your reach. From some drumming I'm drawn into the bass drum. Listening to you, I usually hear the top more — the ride cymbal, the higher tonal drums, and a lot of activity. I know the depth is there but my ear is drawn to the snare and hi-hat, up there . . .

RH: Okay. yeah, I can speak on that a little bit. I never did really play the bass drum boom-boom-boom-boom anyhow. Even though I'm sure there are people who like that and need that and want that, definitely they're not going to get it here. I use the bass drum, it's more so felt than heard, except for accents, naturally, and I deal with it as such.

HM: I told my students this guy I’m about to interview has spent his life — How do you hit it? — he has more experience hitting that ride cymbal than anybody since--

RH: Jo Jones was the hi-hat. Even though he played all the cymbals, the hi-hat was what he got best of all. When he would sweep it, it was loose — rather than chip-chip-chip, tsiss-tsiss-tsiss — it was chissch, chissch-chissch. Getting back to somebody describing my playing, the instrument, even [saxophonist John] Coltrane, what he had said, that we have a way of spreading the rhythm. Somebody once, there was a writer who'd heard me with Coltrane in Chicago -- I may have said this to you, I've said this to different writers, and I don't know that I can call his name, if I called his name you'd probably know it, I don't think he's living now --

HM: Don DeMicheal?

RH: Oh, you’re fast, you get ten points for that. Okay, so he after he heard us play he said, “I didn't know you could play liee that.” And my statement back to him right away was, “You shoud have asked Elvin.”

So this guy calls back Coltrane later -- Coltrane told me that he called him up, and he asked, “What's the difference between Roy Haynes and Elvin Jones?” And Trane told him — and he put it in the magazine — Trane's statement was, “You know, I like them both, boom-boom-boom-boom-boom, they both have a way of speading the rhythm. and Roy does it this way, Elvin does it this way.” He both described it. and to hear somebody describe it, what it is you're doing, you know you're doing something, you know what you're trying to do -- at least, myself -- and I don't put it into words, I don't know how to put it into words. But I liked the way Coltrane had described it. There it is. [Note to editor: Find this quote.]

[Bassist-composer-bandleader] Mingus used to say about me, Roy Haynes, you don't always play the beat, you suggest the beat. Which is a way of, another way of, describing what I do, I guess. The beat is supposed to be there, anyhow, within you, within everybody that's there, once the tempo is established. everybody who's on. You don't have anybody waving a stick at you, or counting for you — that beat is supposed to be in you. Sometimes I figure if it's there, you just accompany the person. You don't have to say “one-two-three-four,” you're playing should say that with whatever you're doing, it should just be there. So sometimes I leave that and play around it. I'm still thinking in terms of one-two-three-four anyhow, or one-two-three/one-two-three, or whatever the meter may be.

HM: The spreading of it -- you've got not a real tight-focused sound -- your whole kit works together across the arc of it.

RH: But then again it has a lot to do with who you’re playing with. You can't do certain things with certain people, cause its may not work, it may make you sound horrible. I do't want to call names or go into it that way. But I'll go back to this: if Jo Jones is playing the Basie thing, p-chisssh, Count Basie is leaving room for everything to breath, the hi-hat and the bass and [guitarist] Freddie Green is there, the pulse — you know what I'm trying to say. You try to surround yourself with guys who are going to try to compliment what you’re saying musically.

That's why I have so much fun, man. Now, in this period of my life, when I get a bunch of guys together — quartet, quintet, whatever it may be — there has to be some understanding there, then you can go to the moon. And what's great about that is there's an audience for that. Because you can take the audience there with you. And it's back and forth. And that's what's been happening in a lot of my gigs all over the world. Somebody will say, “Well, there's no market for that, we can't do this” --bullshit. There are people there, man, young ladies and menand all, smiling and everything in the audience, young and old people, you know? That's been proven througout a lot of my engagements.

HM: When I pulled out the CDs I have, from Equipose to the most recent records,

there's a consistency to the programs. You want to keep it lively, not a lot of balladsa, maybe for variety, but up, and , , ,

RH: I like to get in the middle of it. Medium.

HM: It doesn't have to be super-fast, but you like everybody communicating in a pretty brisk way . . . You don't want anybody lagging behind.

RH: Yeah, that's it. Because you can lift up a room. You can lift up people with the music, if it's tight, everybody's saying something, nobody's depending on just one person -- like the old days, depending on just the drummer to carry y’all --I want people to carry me as well. You know? Yeah, that makes you sound better, I think. Inspires you.

HM: Is there a difference between a Roy Haynes-led record and a CD you’re on -- whoever’s leading it, it seems you’re an equal participant.

RH: I would want to be, yes. I wouldn't want to play on a record where the leader or whoever the record date belongs to has a certain thing for me to play. You can get a lot of other people, a lot of great drummers to do that. Especially today, you can get guys who can read anything, remember anything that you want them to play. So if somebody -- usually people get me for what I do. If somebody's going to hire me for a date, or to do just that -- no, get somebody else.

That has happened, but it really doesn't happen too much. Okay, a lot of the stuff with strings. Sarah Vaughan with Strings, Charlie Parker with strings, there were some parts there. But there's a lot of space in there. too, a lot of space for you to use imagination, and -- I probably would have played more things with the ensemble than they would have written, anyhow. In the old days a lot of things weren't written like that, you had a drum part as a guide, more so. I couldn't see that far, anyhow, so if they wanted someone to just read the charts -- there are a lot of great drummers out here who could do that, at a drop of a hat. [Laughs]

HM: Drum improvisation in such detail began with you and your generation, don't you think?

RH: I wouldn't say it began with me, I'd say it happened way before. Duke Ellington's band, I don’t think there was no music for the drummers. I know, Sonny Greer, back in those days --

HM: But he wouldn't be as busy as you, or Max Roach, or Elvin.

RH: Speaking of Roach, he filled in with the [Russell] band, I don't know if it was the Paramount Theater in Brooklyn or the Paramount Theater in New York, Manhattan. So he filled in with the band. And he was looking for some music. There was no music.

HM: I’ve always thought when the band got smaller the drummer played more --

RH: You're absolutely right because with a big band, you naturally got to hold them together, so to speak. But in my case with the big bands, the first trumpet player, he and I would be close. He would sit next to the drummer usually, the first trumpet player. And you work from there. Each section -- there's a guy playing the lead alto, and all of that. They've gotta understand your concept. I even filled in with Basie's band a couple of times -- and it worked! Everyone was happy, man!

HM: You would play to support the different sections, or as if it were a combo?

RH: Certain things I probably wouldn't take as many liberties with the big band, unless I've been working with the band awhile. Then I would sometimes lead into certain passages that the band is gonna play, build up to it, and I might play something funny in there before, to lead into the passage.

HM: But you would know what you where up to.

RH: Getting back to that first trumpet player again, he would have to be really hip to you and would come in strong, and bring the rest of the band in. And the lead alto player, too, but it was mostly the trumpet player in the back that I would work with. I don't have to do that too much now. I don't worry about that — I have little bands, little bands.

HM: There aren't many big bands to work with that way -- you might sound great working with George Russell [composer-aranger-theorist], for instance.

RH: Pretty intricate, George Russell, pretty intricate.

HM: Did you record with Mingus?

RH: I never recorded with Mingus, but he used to hear me a lot. In fact, we worked together with Bud Powell in the early '50s, '51 or '52, I forget exactly. Mingus and I wouldn't have gotten along anyhow, on the bandstand.

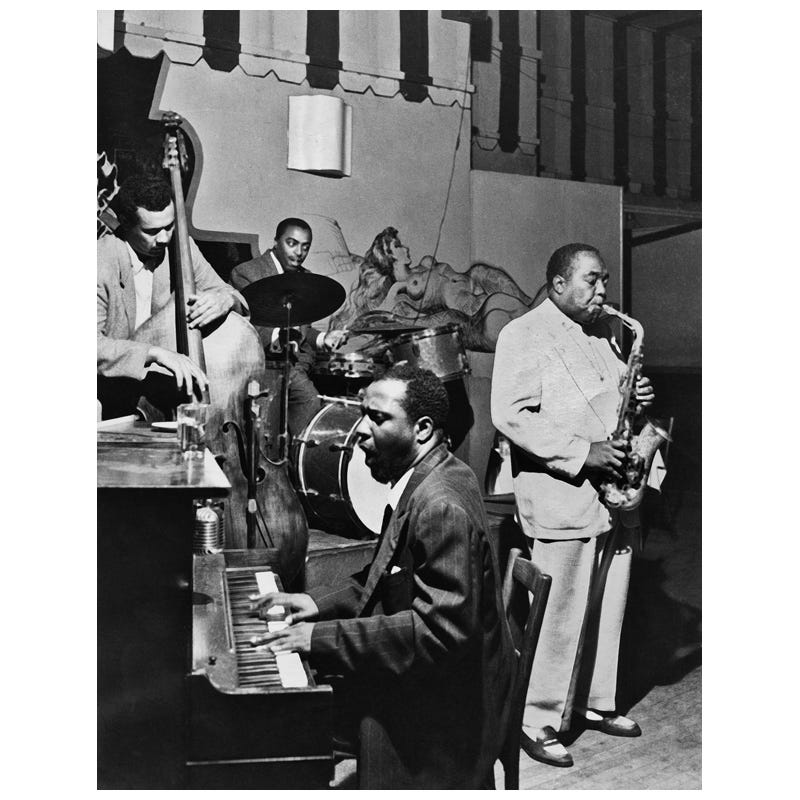

[Bob Parent’s photo: Charles Mingus, Roy Haynes, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker; https://store.irequireart.com/product/opendoor/]

HM: Were you friendly with Dannie Richmond (Mingus’ long-time drummer)?

RH: Yeah. I heard Mingus say once he was the leader of the band. I agreed, too. I really agreed with that.

HM: Dannie had like an athletic thing, like Steve McCall — like a tennis player, a way of phrasing in a quartet, maybe more like a trumpet player--

RH: You mean playing along with the horns?

HM: Not so much in support --

RH: He'd be playing the same line the horns would be playing?

HM: Even his breaks were like a line, tonally, instead of a division of time . . .

RH: I can't really speak on that, this playing the way you’re describing it.

HM You mentioned that you’re into lyrics. When you accompany a singer, are you playing the song?

RH: No, I separate them. I'm into lyrics, anyhow. I don't know if it has that much to do with my playing, I don’t know. I just dig lyrics. Great lyrics. I don't like that A-B-C shit. They have a lot of songs that don't go beyond B-C-D.

Melody? Naturally. I mean, we just did a concert at the Hollywood Bowl, and Herbie Hancock was there with his band, the all-star group remembering Bud Powell, with Chick Corea. Kenny Garrett was on that one, Wallace Roney, Christian McBride -- and after we came off Herbie I guess was listening to it on the monitor in his dressing room and he thought it was beautiful. He said, “Yes, man, your solo was so melodic.”

The drums, I tune my drums anyhow, and I had three racks with five tom-toms on this tour. I tuned them all the time, constantly, if they were out of tune. I don't just tune them looking, but if something is loose, I check them to see which lug is loose. If no lugs are loose, I leave them the same. So the melody is there.

HM: You tune 'em to what you think they should be?

RH: Exactly. Not to a pitchfork. My ears are a pitchfork. and not certain notes -- I just get an idea of what I want to hear.

HM: Do you do that conscious of particular people who will be on the set?

RH: No, I'm thinking about the music, not about them individually at all when I'm tuning the toms. Sometimes I’ve got different ride cymbals and I may think that way. In fact, I have two flat rides with me, a K and an A, both Zildjians, and the new one I didn't use. I brought it out, and I was hitting it one day at sound check. Wallace was there, and I asked him which one did he like? And he said, “That one, the one that you're using” — the older one. but I thought of the other one’s for saxophone, anyhow. And I sort of introduced the flat rides away back in the '60s, I had one on Now He Sings Now He Sobs.

HM: What does the flat ride do that the belled ride doesn’t?

RH: It's just something I hear, and it's become part of me, part of Roy Haynes, now, when you hear that.

HM: You play the edge only, or — ?

RH: I play the cymbal. I try to play all over that motherf’er. What I really try to play on the cymbals and the drums is to draw the sound out of the instrument. Whereas some players beat the sound in. It's called beating the drums. I try to hit the drum or the cymbal in a way that I can get the sound to come out. That's my approach. Trying to get the sound out -- dancing with it. And air -- I leave space sometimes, which is very important.

HM: It's not a barrage, but very dense, active. I don't hear often — well, sometimes — much brushwork --

RH: It's probably for a ballad, appropriate, so I played brushes. Brushes were very important. I played with Sarah the slowest brushes in the world -- because she sang the slowest ballads. It was like one-(sigh, sigh)-two- (sigh, sigh) . . . You had to make that shit sound full, and I played wrong. I played the brushes the wrong way, I was leading with the left hand, and making the swirl or the circle with the right hand. which I had never even seen anybody do before. I can't do that now, I could do it then. I'm not left handed -- but I keep that active with the sticks.

HM: Doing a swoop with the right hand was a way of slowing it down?

RH: No, it was my way of keeping it full, full . . . ‘cause when it’s slow, it can be a lot of emptiness. And I find today that some of the bass players, most of I hate to say the “younger” bass players so I say “newer” bass players or something -- when they play a ballad they don't have that, They can't hold the notes and make it full. Because if a drummer's playing light when you're playing a ballad . . . Some people don't like to hear light, even on a ballad they want to hear a heavy stick, or with a double feeling. But that shouldn't have to be all the time. You shouldn't have to play slow and make it sound full and make it sound like there's some feeling in it. Just because it's slow, it doesn't mean it shouldn’t have any feeling, it has to have some intensity in there, you have to figure out a way without doubling the tempo or something like that. That's my feeling, anyhow.

HM: You hear the whole kit as an orchestra that way -- you should be able to do anything an orchestra can do.

RH: To some extent, yeah. There's something there, each one of those drums, each part of those drums and cymbals you can do something with musically in there. I can't break it down but I can think about it as I'm listening to something, and as I'm playing, I'm searching, I'm looking.

I had five toms, three racks, for this whole tour. I'm now with Yamaha you know, it will be a year and a few months and I was with Ludwig all those other years. Yamaha wanted me way back in the day, they made drums for me, but I never went with them. So I've gone with them now. I have several sets of drums at home, and I just wanted to try some stuff. I had a hard time at first, I had a hard time getting that extra small tom-tom to fit in so I could reach my cymbal on my left, but by the end of the tour I kind of had it. Three in racks, and then two toms on the floor. I don't remember the sizes — I never remember the sizes -- maybe 8 by 12, 9 by 13, and then the smaller one almost little bigger than a bongo. That's starting to sound good now, at first it didn't sound too good. And then there's a 16 on the floor, and a 14 on the floor.

And I just got a new tympani -- a Yamaha tympani. I use it if I'm playing a club someplace, mainly in New York. I used to take it on the road years ago, in the '60s. I had a fiberglass Ludwig tympani, I still have it, in fact. I had it at the Vanguard not the last time the time before. Sometimes there's not enough room. There's no depth on the stage!

My bass drum is 18 inches, so that tympani is 23 inches. There's to set it up, I need more depth. I had it set up so I could hit it, it's way on my right. it doesn't have a pedal, it's “hand-cranking” it's called. You can only use one hand if you’re using the other to change the pitch while you’re playing it. Sometimes I would just keep the same pitch and just play it as part of the set, when I wanted to get down there, play low. [Tympani solo in “Trio Improvisation, Pt. 2, with Chick Corea, Miroslav Vitous]

I use sometimes two crash cymbals -- I had on this tour, two flat cymbals and one flat ride, so there were three cymbals, plus the hi-hat. All Zildjians. exclusively. and a new Roy Haynes drum stick, which is equivalent to about a 7A.

It's been out just this year. It's a medium. Maybe some rock drummers would say it's light, Or drummers who like big sticks. When you play with heavier sticks the work is easier for you. With a lighter stick you have to work harder. I added a half an inch to my old drum stick, so it's a little heavier for me. The length of the stick, I added a half- an-inch, I put it in the back, so the front is the same. I put it in the back, the half-an- inch. Length, I guess when you play the cymbal or the drums you're going to get a bounce -- and some of it's going to help. It's like balance, equipoise, equal distribution. And the way you want some weight to feel.

I know one time, when I had the Hip Ensemble back in the ‘70s, one of my first gigs was a place callad The Scene, on 46th street. The Scene was an acid rock place, but we played there. I remember opening night Chick came down. He had heard my band rehearsing and when he heard the band opening night he said, “Oh, man, you really can put a band together.” This was before his Return to Forever, if I can remember correctly. George Adams was with that band [on tenor sax], and maybe Charles Sullivan was on trumpet then — it was bfore Hannibal [Marvin Peterson]. I had run out of sticks, or my sticks were all broke, or something. so they had another band there, they had rock bands in there, and I used one of the rock drummer's drum sticks, and I says, “Wow, it's easy playing with these sticks.” I'm still learning, you know! Playing with these sticks, I don't have to hit the drums too hard. They didn't feel too comfortable, but it was easier.

HM: A wider drum stick feels easier?

RH: With my approach to the instrument, trying to draw the sound out of the instrument, you don't hit it hard, you have to hit it a certain way — boom [imitates a short, dry decay] and it's there. Touch.

HM: It's as important to a drummer as to a keyboard player or a bassist.

RH: Damn right, certainly it is. Proper touch will take you a long way. It will lengthen your career.

HM: It gives you more variety, more range. Chick as a keyboard player --

RH He has a touch, he has a great touch, so he's easy to play with like that. He plays percussively, too. Not percussive: Forceful. See, I'm no good at the words,

H: You do pretty good.

RH: But I hear like a staccato type of thing and legato mixed, but not all legato. Percussive in there.

HM: Articulated?

RH: Yeah, okay. Chick has a good touch on the drums, too. I had never realized he made a few gigs on the drums up until a few weeks ago. Bud [Powell] played percussively [in that way] earlier. In the '40s. after they had put him in those hospitals where he stayed for a while, those institutions and such, they took a lot of that out of him. But those dates I was on and before that -- '49, yeah — he could play an intro, man, he could play an intro so percussive, and put you right into the tune. Like okay, you have a pianist now, say play me an either bar intro or 16 bar, they sometimes don’t seem to know what to do. But in those days, you’d tell a guy and they were all inside of it man. That makes you want to play, you know what I mean? The fire was there. my God!

HM: Do giants still walk the earth?

RH: They're talking a lot! It's a different world, man, a different world, now. So the way everything is set up, people are different. Generally speaking, people when they're born now they're faster, they become grown quick, and sometimes quality is not important to the word these days. so you get a lot of junk, man -- junk food, junk clothes. It's a very synthetic period. not everybody, but . . . I don't know, I don’t know if we'll ever have any people like we had any more. It's kind of sad, but I've been playing 50 years and I've seen people come and go, and I'm sure the people before me, the ones who are left . . . That’s why when I go different places with my group — or maybe I notice it more with my group — I'm feeling the audience. I'm seeing what they like, and there's an audience here for good music. Good music. Now, who am I to say what's good and what's bad? But if you're playing it and playing it with quality, there’s an understanding of it. The people, when they leave, say all sorts of good comments. You can see it in their faces, you can feel it when they're leaving. They're saying, “Wow, it's wonderful!” The time is right, but a lot of people are trying to wrong the world, including music and everything. They have a lot more to learn [Laughs.]

HM: On a commercial side, business doesn’t value quality, but jazz musicians go into jazz to be quality people. \No one goes into jazz to make a million bucks --

RH: You say so, but I've seen some of them who get rich overnight, and some of them, their names put out there overnight in a lot of instances, and some guys are still in school -- a record A&R man or somebody's ready to sign them up, and they're still in school -- and they want that. They want them before they become professional. Then sometimes that doesn't work. Sometimes — I don't like to call names and get into things — but some peoples managers call me up and want me to record with them, or they want to put it in their bios that they played with me, or all that. After Art (Blakey) passed away you’d be surprised. Some of them wanted me to have a band like that. I'm not interested in having a band just to have a lot of players who sound good --

HM: Who sound good at what?

RH: Like Art Blakey! They wanted me to have a band like that -- even my agent in france, they wanted me to have a band like that, The guy that was booking Sweet Basil [NYC jazz club] wanted me to go in with his band [the Jazz Messengers]. Im not into that. And that's what a lot of those people just want, to come to your band to put on their bios. They want to play in your band because “He played with Coltrane” or “He played with Bird,” or “He's one of the ones left — the link!”

HM: There's this consistency in your bands. They all sound kind of like the Hip Ensemble.

RH: Yeah, yeah — and on the minute. And these guys, we still play together. I don't want to have a band now where I keep the same guys and I work all the time. I haven't wanted to do that in years, and I haven't done it -- and it feels good this way. Sometimes I get Craig [Handy] or Don Braden or Donald Harrison [on saxophones], David Kikowski or Darrell Grant as keyboard player, and a couple of different bass players — Ed Howard or Dwayne Burno — and it feels good. Everyone's always glad to come back, and it feels good this way. We can play the same songs we have, and make them sound new and fresh, fresh as hell.

HM: You’ve had long associations, like with Chick, Sarah, Lester --and I don’t know — Gary Burton?

RH: I have done anything with him for a long time, but I think maybe we're talking about dong something with Chick, and maybe Pat [Metheny] included, I think there's some talk about something like that. I hadn't played with Chick for a long time until this tour. Not for years, since Trio Music, on ECM, in the '80s. That may have been the last time. It's ‘90s now, its been 10 years. And we had some exciting moments in this past tour. It was great, man. Mostly every night, different audiences, different places. You know, we recorded already, this all-star thing, for Stretch. I think it’s coming out on Concord.

HM: Stretch is Chick's label on GRP --

RH: It was GRP, it's not now. I listened to it for the first time yesterday, the night before last. I couldn't listen to it by myself. I had to have somebody there who knows something about music, a little bit about music. I got this guy who writes music, he plays saxophone, he writes for rock and rappers and all of that, he lives out my way [in Jamaica? Queens?], and it's interesting to see what he likes. He says, “Man, I like that!” It's interesting. what he responded to. We did all Bud [Powell] tunes but one that's not, I think that Chick wrote. The Bud tune that impressed him was one called “Mediocre,” and it sounds like [Thelonius] Monk. Wait til you hear it. Wait ‘til you hear that one.

HM: Is it a broken-up tune, angular?

RH: It's just a simple melody, but, no, it's not that simple a melody either, because it has some odd notes. Monk and Bud were very close, anyhow. You know, it's something to have played with both of those guys. You know, looking back: Have I had an interesting career, or what? I mean, could it have been any wider? Look at it! I played with Louis Armstrong on the road for one week, with the big band. That's without rehearsing or anything. In 1946. I was still with Luis Russell. We had a week off. We went down South, to Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, that was one of the places. There's two guys still living that I know of who saw me with [Armstrong’s] band -- one is Jimmy Slyde [tap-dancer], he was going to school down in Raleigh-Durham, and there's another guy who was a professor. I stayed on the campus. You didn't make money in those days, and to go down South, where you gonna stay, a black person? We played tobacco warehouses. I know there were a couple of them that were tobacco warehouses. They had dances, and things like that.

HM: Integrated audiences?

RH: I don't think it was integrated. No, this was a Black affair, if I remember correctly.

Pops, he was great. He didn't have much to say, because the first trumpet player, he was named Fats Ford [Andrew “Fats” Ford], he changed his name to Merenguito, because he was playing up in the mountains, playing with the Latin bands and all that. He was the one I sat next to, and he hipped me to the different arrangements, different things in advance.

So — to have played from Louis Armstrong to Pat Metheny and a lot of people in between. There are a lot of people I've forgotten I've played with. Arvell Shaw lives in my neighborhood, he and says, “Roy, remember that time we played with Sidney Bechet?” I forgot about that! One night in Boston we played with Sidney Bechet! So you know what I'm talking about -- Here's a guy who’s 71 year old, who's played with all these different people, who's still playing — Man, you know who the guy is I'm talking about! He's sitting right here next to you! I’m 71! The encyclopedia [Leonard Feather’s?] says the wrong thing. I told him [editor Ira Gitler?] to change that a long time ago. March 13, 1925, two o’clock in the afternoon, Friday the 13; my mother told me. Make sure you put all that in!

That’s what Bud Powell said, when we did that record in 1949, the one with Fats [Navarro, trumpeter, as well as Sonny Rollins, sax and Tommy Potter, bass], Bud Powell said then — I can't say the same words he said cause you wouldn’t put those words in the magazine — anyhow, he said, “People will be playing this shit ten years from now. That was 1949, and we just went on a tour Remembering Bud Powell. 1996. For good example. And before we went onstage we had a tape that would be playing by Isaac Hayes [soul singer-producer] talking about Bud Powell, and they'd play some of Bud Powell's cuts, and there’s one cut they played I was on, you could hear the hi-hat -- every time we listened for that, before going onstage I thought, “Oh, man, here's this guy, standing in the wings listening to his old self, half a century ago!”

Oh, man, that in itself is kind of unique. I feel like I've been here a long time ago and I've back again. I feel like I've been born again, and I don't know how that feels, but that' s how I feel. Its' weird. To have been around somebody like Lester Young, I stayed with Lester Young for two years, from 1947 to 49. and I was around him, listened to him talk. And around Monk. Monk didn't always talk too much. Around Bird. I started working with Bird in '49, and, well, we didn't work steady in those days. And then around Coltrane. Just to name a few people.

HM: Who have you missed that you would have liked to have played with? Hawk?

RH: Who?

HM: Coleman Hawkins?

RH: Yes! let me tell you a short story: I forget what year it was, let me think where I was living . . . Must have been early '50s. and Coleman called me up. He lived up in Washington Heights, Sugar Hill, in an apartment called Kinghaven, where I thought he belonged in it. The Kinghaven Apartments. And during this time he had a green convertible Cadillac. He told me has a gig up in Taunton, Massachusetts, and I'm going to make the gig with him. My drums are going to come in the back of his Cadillac -- you know, they had big trunks in those days. So I was in the band, I think it was [trumpeter] Kenny Dorham, I was riding in his car, I guess we had the bass in the car, you know cars were big then, and we're driving from New York. I had a car, and left my car, went in his car, naturally. And we got to Connecticut. Coleman's driving, and I said, “Hey man, I’m a little hungry, maybe we should stop get a bite to eat.” So we all stopped, and we all ate. When we got to Tauntonm, Mass, we're a little late, and the union man is there. Evidently they docked Coleman, and Coleman took the money out of my pay, and during those days, I wanted to kick his ass, man. I was going to make all his tires flat, get one of my hoodlum friends to, I wanted to kill that motherf'*r. I didn't even come back with him, because my brother was there and I went back to Boston. that was my exeprience, the one night I played with Coleman Hawkins. I don’t know, maybe I played once before that with him on 52nd St. I’ll say this: One of my favorites on tenor sax was Don Byas. Even as a teenager I used to listen to Don Byas, man.

HM: He combined virtues of Lester and Hawkins, didn't he?

RH: And he played with Dizzy [Gillespie], too, didn't he? I played with Dizzy a lot of different times. I never worked with Dizzy steady, but the thing at Birdland, Bird and Diz, I'm on there [???]. Then I did some stuff with Dizzy later. Later in my career.[Chuckles]. Dizzy used to have this cymbal he brought to the gig, he wanted the drumers to play. Billy Taylor [pianist] reminded me of this story, Dizzy wanted me to play this cymbal, and I told Dizzy, Man, go and play your trumpet, play your trumpet! I was so young, me telling Dizzy -- “Man, play your trumpet!” It was a funny cymbal, too, a sizzle cymbal. He used to have a drummer from Philly, he used to sound good with it, but I don’t care, what the fk--I'm Roy Haynes, I trying to get my sound and shit together. I forgot all about that until Billy Taylor told me about that. I said, I was a damn little youngster.

I'm good, man. I just got to get up. What happens, when you do an interview with a man who’s been playing 50 years: They go back, I get involved in the shit, I'm reliving it when I'm talking about it, so I got to get up now and again. Damn.

HM: You got a sizzling sound.

RH: That has to do with the cymbals, I think. Pat says that flat ride has chords in it. He hears things in it. So I've got a few of ‘em, I made them give me a few of them. I'm reliving that Coleman Hawkins shit, and the Dizzy shit, I had to get up. [He stands and stretches]. I never did answer that question, I thought you were going to ask me that, too.

HM: Didn't you play with Miles?

RH: Miles? Didn’t you know . . . shit. Miles used to say — It's a funny thing. On this tour I learned a lot. Wallace [Roney, trumpeter] told me that Miles told him — Wallace got very close with Miles in his last days. and he told me that Miles told him about me that Bird stole his drummer. I said, How’d you know about that? You know. Because I was with Miles before I was with Bird. At Soldier Myers in Brooklyn. Does the name Norby Walters ring a bell? The last time i saw` him was at a thing they had for Miles, at Radio City Music Hall? After that they went to a place on 57th St. called, some after-hour place --- Norby was there. We worked for his father. His father was a ex-fighter, had a place in Brownsville, Brooklyn -- Sutter Avenue. You familiar with Brooklyn? Soldier Myers [???]s. My wife was from Brownsville. It was Mafia. Hebrew mafia.

HM: Not my people.

RH: Norby, he started getting involved with fighters. He was a young kid while we worked in his father's place, and he became big in the business. When they opened, Soldier Myers opened with Miles Davis with Sonny Rollins. I think first we had Sonny Stitt, then we had Sonny Rollins. We had Tadd Dameron, we had Walter Bishop on piano, cause we stayed there maybe two weeks or so. And -- yeah. Miles had quit Bird at the Three Deuces to make that gig and got me as his drummer. And then when that gig was over — how did it work? — we went from there to the Onyx club on 52nd St. which had changed its name to the Orchid Room, and Monty [??] was booking in there. Monty got me Bud Powell, and then we went into the Orchid right after Miles' gig. so after that Max Roach, he was from Brooklyn, he was going to get his band in Soldier Myers. So Max offered me the gig with Charlie Parker. So it was a turnabout. Miles always said later, Bird stole his drummer.

HM: What about Miles’ late '60s thing?

RH: Actually, I was supposed to come in after Philly [Joe Jones, drummer]. Who called me, Hal Leveatt [sp??], his manager, and then I think Cannonball [Adderley] was there, Jimmy Cobb was his drummer, that's who went. And one of the last times I saw Miles, we were at the Grammies, and I think both of us had won a Grammy that time, when he saw me -- we were leaving before it was over -- and the lady that was with me, he had recognized her always, he said, “Haynes you live out here?” He wanted some company, I guess. And I said, “No.” He wanted me to make a record with him, and I don't know which record it was going to be. My answer was, “Do I have to play a backbeat?” He said, “Play anything you want.” We didn't get together, though, after that. We recorded something in '51, with Sonny Rollins John Lewis, Percy Heath. “Down,” “Morpheus”. He was real sick then. You remember that date? And he did “Blue Room”. He was real sick on that, I remember because it didn't happen. But “Down” was good. Sony Rollins was on that, too.

HM: The backbeat thing would have been retro?

RH: You know the period I'm talking about?

HM: After Tony Williams, like the '80s --

RH: I'm talking about the backbeat. What's the drummer who got in some trouble in Japan, who was playing with him?

HM: 1980s — John Scofield and that band? With the saxohonist Bll Evans? Maybe Al Foster?

RH: Yeah, okay, maybe it was the late ‘80s. I was just jokin'. I don't think Miles would have wanted me to be on a date. But he was one good for suggesting drummers what to do. We were close way back. In fact, we bought our first cars in summer of 1950. We used to race through Central Park, and shit, late at night, I had no driver's license, we used to bang them up! And we were also listed in that Esquire magazine, we were the only musicians listed in that for wearing clothes, this is when we were having our suits made, which I still do, He did right up until the end, so -- I was always into clothes, man. Clothes and cars. Always, since I was a teenager. I used to come to New York City from Boston to shop when I was a teenager, just for clothes. They had a lot of slick stores up at 125th St., and I'd bing the stuff back to Boston and they'd say, “Where'd you get that? “They didn't have any of that shit up in Boston, not at that time.

HM: Do you still shop a lot?

RH: What I usually do, when I get something made, I get material and then get the tailor to make something. I've got stuff all over my house, clothes every damn place, man, I've often thought of putting something in the paper or on the radio, or just come on down to the Bowery and give away a lot of clothes.

HM: I'm going to be there.

RH: I may do that shit. Maybe they’ll advertise it somewhere. Sit in a limo . . . A lot of people would take the stuff and sell it, if they were to know I was going to do that, but a lot of needy people could use it. And the car thing, automobiles -- I’m going to have a car in a show this Sunday. It's a Bricklin, 1977, with the gull-wing doors, It's a bad

car, it stops traffic. I drive a convertible Corvette, I drive that periodically. Today I'm driving my Cadillac Biarritz Eldorado. So now, that's my hobby, I put my cars in the shows, I win a trophy, it's a lot of fun. I don't work on them, I bring them out.

HM: I could have heard you with Miles on Bitches Brew, somethng like that. You were playing jazz-rock way early.

RH: I was?

HM: Yeah, when you were playing with Gary Burton and Larry Coryell and all.

RH: I keep forgetting about that shit. You know, we did some things down there with some of those string guys, too. In Memphis and Nashville.

HM: The stuff sounds corny without you.

RH: You think that's corny, Barefoot Boy, [guitarist Coryell album] that's corny? I heard that shit one night, there was a long drum solo, like a vamp there. I was into it.

[Roy Haynes driving “Gypsy Queen” with Coryell, guitar; Steve Marcus, soprano sax; Lawrence Killian, conga; Harvey Wilkinson, percussion; released, 1971]

HM: The Free Spirits, that's corny ...

RH: Did I make it? Oh, I thought you were talking about something I made.

HM: Tennessee Firebird [Burton, Marcus, Haynes with noted “country” musicians including Chet Atkins] sounds like it could have come out last year.

RH: I forgot about that shit, damn. Speaking of Coryell, lots of times I read someting about myself and who I played with, and I seldom see Kenny Burrell. and I played a lot with him, too. Even recorded a Vanguard thing, Men At Work. I think that's one of the things Pat Metheny got hip to Roy Haynes through -- Men At Work.

Out-of-print jazz guitar trio classic

I think Kenny Burrell's been overlooked a lot. They used to say that about me. They don't say that now. You don't hardly hear too much about Kenny, though. either with the musicians or the writers.

HM: People take him for granted, I guess. Maybe he’s a quiet person?

RH: There has to be someone out there who has a low profile they talk about.

HM: When someones eccentric or reclusive, they make for good copy.

RH: That's why Mingus got hip.

HM: Arcbie Shepp?

RH: But it didn't last. See, when you get some shit . . . That’s why I say I've seen a lot of them come and go. You see a lot of them, hot for a season or a year. Drummers are just general players.

HM: Anybody, in any career.

RH: That's true to some extent, but then there are some who keep going no matter what. You don't see ‘em much, but then their name pops out. Sometimes . . . it’s something to think about. Sometimes people can be frightened of a certain person: fear. I've checked that. Knowing you’re doing something, and knowing you're going to get little credit for it when they've peeped it and they know about it and jumped on a little of that bandwagon, “No, we can’t say him”-- then whe you're dead they talk about you. In some cases. Only the strong survive, You can't keep a good man down, with those cliches --

HM: Are you thinking in terms of white musicians, who copped a bunch of stuff that the innovators didn't get the credit for?

RH: I wasn't going in that direction, but there might be something there, too. Because a lot of peple who don’t play any instrument, there's a lot of fear there. They need to learn a little more about life, that fear of people. [Saxophonist] Lucky Thompson, that guy could play his ass off -- just a nice playing cat, but he didn't smoke or drink. When I came to New YUork I didn't smoke or drink, neither. The moment was driving me crazy. I started doing everything in the '60s. I got too wild in the '60s. Talk about “Hip Ensemble”.

The Hip Ensemble -- one of the gigs we played was Carnegie Hall. I saw the guy at Newport who first started talking to me about videos. Video’s going to be the thing! He was right, and I told him that. There used to be a place called the Cleopatra’s Needle, that's where we rehearsed in the windows to play at Carnegie. George Adams played, I think he had a bassoon on there, Shepp had his group, Tony Williams had Lifetime, I think it was Weather Report. 1970, '71, ‘72, whatever — I forget. So we get a standing ovation. When I saw George Adams later I said, “Hey, man we got a standing ovation.” He said, “Lot of groups got a standing ovations.” We got a good review in the paper, shit like that.

I'm telling you this story for a reason, I forgot what the reason was . . . but anyway, I would come out of a drum solo and go into what was called the Negro National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice” -- we even did it on the record. Years later, when I dropped the Hip Ensemble, a lot of people said, “Roy Haynes! Hip Ensemble!” When I had it, even some big people, “Yeah, yeah, Hip Ensemble!” We were doing good. I was getting a lot of gigs, getting record deals. We were on Mainstream first, I coud juggle a lot of gigs then. We didn't make a lot of money but in those days you didn’t need a lot of money.

So it was good. The first record released, it got five stars, but the guy who wrote it, I don't know, I think he might have got some money, for the same magazine, too -- so we can't say. But he wrote, “Being hip has always being one of Roy Haynes’ problems.” I said, “What? Who is this guy? He knows me, or something?” Joe Klee — is he still living? Got five stars, I can probably still find the review somewhere. I had two on Mainstream. Equipoise was a nice record, too. Oh, so this is a reissue [looking at a CD version]. The color was in color before.

HM Ir’s got Leonard Feather’s liners from 1990. The music has a lot of enduring quality. What you going to do next, that's the question?

RH: I'm got some gigs for 1997 with my groups. We're going to Australia. I’m going into the Village Vanguard the 5th of November, you think we can put this in there? The band for that? I knew you'd ask--I'm not sure. I think Darrell's going to make it, but as the Roy Haynes group, I might bring Graham [Haynes, his son, brass player] in there with me this time. I don't know about his availability too much, I'll have to ask him. We were at the Vanguard together a couple years ago, you know. Ae also did Carnegie Hall with me in December. In fact, I may have the same Carnegie Hall group that I had, with Donald Harrison,

HM: I like what Graham's doing, so musical, and original. Do you think you have drummers who are musical children?

Roy and Graham Haynes, from Graham’s website Music Evolution

RH: Just drummers? Are you kidding me? One guy I got in mind told me, “I'm another one of your sons.” You just want me to elaborate? I'm not going to. I'm proud of it, you're damn right, you're damn right, it helps. I could name some of the ones --I'm not even going to do it now.

HM: Tony Williams.

RH: You're saying it -- you put it in like you're saying it!

HM: I will. Tony would, too.

RH: He probably would, in his way. Sure, there are a lot of them, man, I'm proud of that, thats probably one of the things that kept me out here, that's keeping me out here, keeping me, ‘cause I'm still here!

HM: Did you ever spend much time teaching -- or you’re a player, you’re not a teacher, right?

RH: Did you hear me say that?

HM: I said it.

RH: You've said that just now, but I've said it before. No, man, I'm a teacher in my way, they've taught me that. They told me that. That's the best kind. I'm not the type to sit anybody down -- first of all, I don't know that, those kinds of lyrics. I'm a lyricist, but . . .To be a successful teacher other than really knowing what your dong, you got to have gimmicks. You try to teach somebody now -- after two lessons they're telling you what to do. You know? And you got to keep them coming a long time. Stanley Spector, he's not living now, he used to hang out with me, he started teaching in Boston, and he had all kind of gimmicks. You had to write books. I'm a player. and I'm not going to tell anyone to do it this way, because they can probably find a better way than I'm doing it. There's no one way.

I get discouraged, I bought some golf clubs in 1951, and Joe Harris, the drummer, he could play some golf. He discouraged me. He said, “Haynes, don't bend your left arm.” He discouraged the shit out of me. I still got my clubs, but I gave it up. So he told somebody what not to do -- when they could come up a different way, and invent something. It's better to stay loose.

You know, my son Craig plays. He was with Sun Ra. That's my son. He's older than graham, the eldest, there's two boys and a girl, my daughter Leslie. She has three daughters and a son. Her boy's Marcus, and he wants to play drums. Most kids want to play drums. I'm giving him a set of drums. But he has a sister -- he has three sisters, not the youngest one, the middle one, Olivia, I went to her school in May, she played at their spring concert, she played drums and she had a good touch. That was interesting to see, that's my granddaughter, so the beat really goes on, it does.

It doesn't surprise me to see women playing drums, they've got some damn good ones, too. In the ‘50s, with those all-girl bands -- there were some who could really swing and really play.

HM: It must feel great to look back on 40 or 50 years of playing.

RH: Yeah, and it's over 50. I was playing before I got here -- in 1945. This bandleader sent me a one way train ticket -- I'll never forget that. That was Luis Russell.

HM: Was he from Boston?

RH: No, he was from Panama, a New Orleans guy, you know. I think when the band played Boston I wasn't even with them then. If I remember correctly.

HM: Is there a Boston sound?

RH: Some people say that, because theres Alan Dawson, who’s a teacher. He was younger than me. Alan and Tony — Tony studied with Alan, he used to teach at Berklee, passed away a few months ago. He was on a lot of Prestige stuff, was with Lionel Hampton. He was a great drum teacher, and could play, and was a great guy.

You know, people talk about paying respects after somebody passes away. The situation happened for me where the drum company was supposed to have a set for me in Boston, but it didn't happen, it was't there. So there happened to be another set that was rented by the club for an act that was coming in after us. So I played those drums, and they didn't have the pedal I wanted. So right away, Alan Dawson comes in and brings his pedal. I talked about it that night at the club, while he was there and the place was packed,. because it was true. He's a great guy, and I wanted to give him that.

I remember in my travels, I'd be playing with Stan Getz in the '60s, playing in California or anyplace and a cat would come up from Berklee, say, “Alan Dawson told me to always come and check you out,” and that knocked me out. That happened a lot in my career. Alan Dawson was a great guy, I'm glad to say that now.

HM: Also Metheny, and Burton, and —

RH: All those guys are not from Boston, but yes, the school [Berklee] has a lot to do with it. A lot of the guys in my band -- Kikowski went there with a lot of other guys. I got my honorary degree from Berklee, so I'm happy about that, too.

HM: Oh yes, this must have meant a lot to you.

RH: You mean, after all these years? But you need that, you know. I hate to start this without mentioning names, but there was this Japanese gentleman, I can't think of his name, we got honorary doctor degrees together. This gentleman was an inventor of electronic something or other, so he was big. And Joe Zawinul. Joe brags about it, I saw him down at North Sea Festival, he brags about it, had pictures of him and me with gowns and caps! But it was a gareat feeling, because when they announced me getting it the musicians just went crazy. I think yeah my daughter and my son, my brothers were there, from Boston, it was great. I forgot where I was.

Don't ever ask me the year. I know the old year, and this was a few years back, maybe three or four years ago. You thought I should of gotten it earlier, huh? Things like that — I got the Jazzpar prize, where you get some money, I got the NEA Jazz Master award, where the president sends you a letter -- that was after the Jazzpar, which happened in Copenhagen.

One of the things that happened with the Jazzpar, I get a kick out of it, is I was riding on the plane, and Ed Howard’s sitting behind me, reading the International Tribute, the peoples' column, and they'e got names like Margaret Thatcher, and then it comes to Roy Haynes, announcement overall getting the Jazzpar prize — which was so great, because it was international, all over the world. I'm sitting on the plane -- that's a thrill. you get it that way -- and that's not even in my country. but it comes. You stay around long enough, and you get it!

HM: Imagine: When you were playing with Louis Armstrong, those kinds of awards were unheard of --

RH: Yeah, and I was only with Louis Armstrong for about a week, I didn't have time to think then -- but when I was with Bird! and had a lot of time off, and with Pres, two years. These kinds of rewards -- and the thoughtfulness of different situations, different things that have happened.

HM: People taking it seriously.

RH: When somebody stops you, and it can be anyplace -- I was in Athens, Greece one year and somebody stopped me: Roy Haynes! I was on a plane gong to California, and there's a guy sitting in my seat, and I didn't say anything to him but showed him the whataycallit, my boarding pass, so this guy gets up and sits down in the next seat, that was his. So I guess he felt funny. You know, we're sitting up in first class, so this brother comes in, I'm wearing my Western hat, my boots, and this guy sitting in my seat, so after a while, I think I toasted him -- so I guess he felt a little relieved. and he asked me later, “Are you a Country and Western singer?” I said, “No, neither. I'm a drummer. I play jazz.” And he started asking me, I said, “I'm Roy Haynes.” He said, “What!!” It was Matt Dillon, the actor, and you know what, he's got the record Swingin’ Easy with Sarah Vaughan! We talked the whole way and he came over to the Hollywood Bowl the next night to see us! These type of rewards. It can happen anywhere.

HM: The changes you were talking about when we started, the superficiality . . .

RH: I didn't use those words. I did say superficiality. There are some other people coming up. You mentioned Lester Young -- the Art Tatums, the Bud Powells, that’s over I think. Because somebody can decide they want to be something, and they can go to -- we got all these schools. we didn't have these schools in the old days, and you can be taught. We didn’t have that where you could be taught the other way, I don't want to say the superficial way, but where you had a lot of these natural players. That may happen but I can't see it happening that way anymore.

HM: So the systematic way of looking, the self-conscious way --

RH: This is the way the world is now. We didn't have no, what do you call those things, the drum machines. You know, your phone -- it's a whole world that's something else. A genius in another way, but not necessarily with the experiences and senses that invented this music, invented the styles of talk. Stuff that by now has been rehashed over and over and over.

HM: That's what I admire about Graham, no rehashing.

RH: Yeah, he's doing good. The people believe in him, over at Polygram [record label], I'm sure. I heard him on WKCR years ago, it must have been his first interview, and he didn't say nothing about where he was from, his dad or nothing like that, and he wasn't asked. And it was cool. I checked out where he is. He's always been independent since a child. Yeah.

HM: Was he musical as a kid?

RH: I play at the Hollywood Bowl, and I saw [reeds player] Bennie Maupin, who used to play with me before the Hip Ensemble, before he played with Herbie Hancock, either. and he was telling me, when he used to come to my house to rehearse, Graham used to sit down there to listen. George Adams used to say the same thing then, when I started the Hip Ensemble -- we used to rehearse in my basement -- Graham used to sit on the step and he could see something in Graham's eyes. George told me that in the '70s. It’s the '90s now. Did I talk to Graham about music? They used to come to see record dates with me. Graham came to see Monk with me, came to see Coleman Hawkins with me. My daughter, before Coleman Hawkins died, she saw him at the Scene, when they were having Sunday afternoon jazz interactions there. Yes, they used to come to gigs with me, and my oldest one, Craig, I used to bring him, when I was with Sarah, even, I used to bring him, like babysit him.

There was one show I was playing, “The Fabulous Dorseys,” on Saturday nights. They used to have the dancers, those girls. He was little kid, and wow, the ladies seeing him used to go crazy. “Wow, do you have any more children like that?” So they heard the music, my kids. And their mother, I met their mother while I was with Miles. She was from Brownsville. She passed away. My oldest, Craig is just about 40, close to it, so we hooked up in the '50s.

HM: When did she pass?

RH: I don't remember the year. Isn’t that strange?

HM: Like, 10, 15 years ago?

RH: Yeah. And the funny about that. You asked about playing, I was out with Dizzy that weekend, in San Francisco. What's the name of that place, not a small club, like an auditorium, with an international type name. The Great American Music Hall, that's what its was named. And I was out walking, that Sunday, I was out walking because I always like San Francisco anyhow, it was so strange, and that's the Sunday she passed, She was in the hospital, and I'd seen her five days before. She went with cancer.

HM: Plague of our century. You know Roy, I'm almost out of tape. There's no way we gonna get it all, ‘cause it's not over, your life, your career.

RH: The guy upstairs, going tick-tick-tick.

HM: He's given you the time, man, you'er counting time.

RH: It's been great already. You know, at one point I did an interview and said I was semi-retired. Because I was, man, I was semi-retired I said. Yes, I've stopped playing. The drums will probably end up kicking my butt to the end. But the past year, past eight months, it's been so unbelievable man, beautiful, frightening. I don’t want a lot of gigs, but I've got gigs -- to Australia! I've been there before; I've been to Senegal a couple of times, too, played with the great drummers over there.

I brought the Hip Ensemble over to Senegal and we played what is that I forget that place you can take a vacation -- Club Med. We had two gigs: playing a free gig for the natives, and a paying gig they came to. So there was this guy Doudou N'Diaye Rose, an Aftrican drummer, who had several wives, several children, all drummers, a band of drummers, they played with one stick in one hand and they make their own drums sometimes. He didn't speak English, but at one point we were going to play together, and at first I thought he was going to sit in with our group, then I found out I was going to sit in with his group. So we're playing, I’m listening, we're playing, and at one point I heard what they'r doing, one drummer plays background, one drummer plays a solo -- at one point they’re all playing background, and they're looking at me, which means that its time for me to solo. Man, we hooked up on some rhythms — somebody told me later if I wanted to run for any political office, I would have won, right then! I still have some of the tapes and at the end you can hear them screaming, “Haynes, Roy Haynes!” It’s great

HM: I'd love to hear some of that come out.

RH: Yeah.

HM: There are some great Senegalese drummers in town. Mor Thiam? Who worked with Don Pullen.

RH: Speaking of Don Pullen, I just made a movie where we did that song of his, “Big Alice”. With Whitney Houston and Denzel Washington, called The Preachers' Wife, Its' coming out for Christmas, maybe by the time the magazine comes out. I'm in he nightclub scene where they're playing “Big Alice,” and they're dancing. Lionel Ritchie's also in it, he's playing piano, backing her up one one thing we play with her, Whitney Houston.

It's a funny thing, Don Pullen, his girlfriend, his lady friend, she had heard me and George Adams were playing in Spain one year, it was a drum thing, Philly was supposed to be on it, but Philly had just died; Elvin, myself and I think Joe Chambers had replaced Philly on it. I think that's the first time Don Pullen ever heard me stretch out like that, and he never stopped talking about it. So that's why his lady friend said “Don would like you to play on this tune,” I'm sure. But I know him. He used to play organ at a place just down the street from my place in Hollis. When I lived in Hollis. My kids live there now. He used to play organ in there, I used to see him all the time, without even realizing he would come out and end up like he did.

HM: Would you consider doing an African drum thing?

RH: To record? I think I would prefer to do a video like that, rather than just record it for record [audio]. I'd like that to be seen as well as heard. On record, you can't just do all drums all the way through. I mean you can, but I don't think it would have the meaning I would like it to.

In the Bible somewhere it says “All things are possible to those who believe.” I believe it can happen.

HM: That’s a good place to stop!

RH: Agreed.

BUT WE DIDN’T.

HM: Your way of playing in the old days--

RH: You played the hi-hat for the piano, naturally, because Jo Jones did that for Basie, you played the hi-hat for the piano, you played the hi-hat for the trumpet. For the saxophones we used to play the ride cymbal. and I tried playing the hi-hat for some piano players about 10 yeasr ago, and it was not enough for them, they were not comfortable to that, I had to go up to the ride cymbal. Certain piano players you can play the hi-hat all the way through. Like with Phineas [Newborn], with those hands, you could do that, I could do it with McCoy [Tyner], but I'm not so sure McCoy wold be comfortable with that. I mean, I'm talking about some years ago. I don't know about now. But what I'm trying to do now is put the hi-hat back in the picture, not on the two and four, but playing the hat, playing it. I'm trying to bring that back into the picture.

HM: Does is provide a more focused sound? Why don't they like it?

RH: It doesn't always sustain, because it's open-and-close, open-and-close, open-and- close. The ride cymbal sound is open, it's actually looser. But there's a way, especially a way I'm going to try to play the hi-hat, it's back and forth. It's not always the same figure. The figure changes. Sometimes you leave it open a little while -- with rock you can almost do it. You're playing a little funk, you can almost stay on the hi-hat.

HM: Did you every play with a rock band?

RH: No, other than those records you were saying earlier, with Coryell.

HM: Dannie Richmond played with the Mark-Almond Band --

RH: You can't do that with anybody and everybody, as far as play the hi-hat that way, because you know it's not going to fit. But there's a way it can be done. I remember there was one time at the Vanguard with Phineas; I could do that with Phineas, a lot. I remember one time with Bud Powell up at Minton’s [Playhouse, Harlem jazz club]. That could work then. That was probably late '40s.

HM: I can imagine you doing that with Graham.

RH: He may have a certain thing in mind that he would want behind him. I"m going to try it, though.

The record is all finished, shold be out the firt of the year. There's a first section where we do “Glass Enclosure” and from there we go into “Tempus Fugit”, and I play the break in between both compositions that leads into “Tempus Fugit”, and there's a litte hi hat thing I checked out the other night when I heard it. Sometimes I forget what the hell I play, which is very easy, you got a lot of stuff going on in your head, that youre trying to play, you want to play--

Lot of times certain things I make that I'm on — I don’t know. I’ve seen the tv thing, there's a drum thing coming out that I’m in. l I didn't want to watch it myself the first time. I can't explain what it is. Sometimes you want to get someone else's reaction of certain things. It could be that in my subconscious mind. Certain things you aren't sure of or that really knock you out, you want to see if they knock someone else out, too.

There's a drum organization, they did a video called Legends of Jazz Drumming, from the '40s to certain years . . . A lot of drummer are listed. It's hosted by Louie Bellson and Jack DeJohnette, and they wanted me to make some comments on it, so there are two little excerpts of me. That's out on Warner Bros. And the movie's coming out — The Preachers Wife — and the Chick record, the Grappelli record, I've got gigs starting with the Vanguard in November -- and I'm going to Barbados to cool out. I've got to cool out for a while. So I can think!

Thanks so much for (re-)sharing this!

Fascinating. I learned more about Roy from this interview than anything else I've read. Excellent work, Mr. Mandel!