My Keith Jarrett files, 2009 - 2010

To mark the pianist's 80th birthday May 8, an up-close-and-personal interview, phone notes and Charlie Haden’s point of view.

I was first excited by pianist Keith Jarrett when I heard him on Forest Flower with Charles Lloyd’s quartet live at the 1966 Monterey Jazz Fest.

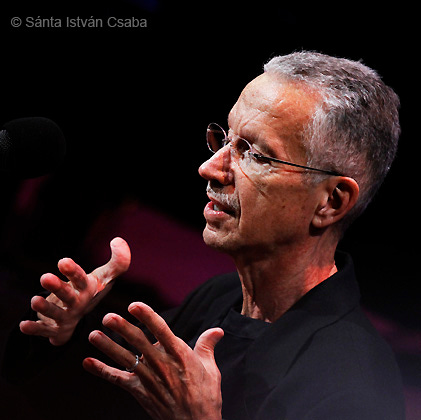

Keith Jarrett receiving NEA Jazz Masters Award, 2014, by Sánta István Csaba

I even practiced his fast flute tune “Sorcery” (not what he’s playing below, but in the spirit).

Keith Jarrett, Charles Lloyd, Cecil McBee, RTB TV Studio, Belgium 1966

Next Jarrett was releasing unconventional albums like Restoration Ruin (1968) where he played everything, wigging out with Miles Davis (and circa 1970, sometimes Chick Corea), dueting with vibist Gary Burton, and on Ruta and Diata (1971) with Jack DeJohnette, surprising in a sax battle with Dewey Redman (check out “Mortgage on My Soul (Wah-Wah)” on Birth (1972). In 1972, releasing Facing You, his first album produced by Manfred Eicher for ECM, Jarrett’s career turned towards epic solo performances, long long-lasting American and European quartets, accomplished classically oriented works, and an iconic Standards trio with DeJohnette and bassist Gary Peacock.

On May 8 2025 Jarrett turned 80. He’s retired, still suffering stroke affects. Not all he’s done over the years has been to my taste, but that’s me. The man has had a triumphant career, leading a uniquely creative and impassioned life. So I was of course thrilled and honored to be invited to interview him at his home in a forested area of eastern New Jersey, some 50 miles from New York City, for the premiere issue of the French magazine So Jazz. The occasion was release in 2009 of his album, Paris/London Testament, recorded the year before.

Though Jarrett had at that time a reputation for being extremely sensitive to random noise, coughs, cameras and similar interruptions during his performances, in person he was charming, relaxed and engaging. We sat in a coach house he's turned into a music studio, he in the engineer's chair of the control booth with a view into a room containing two grand pianos, two harpsichords, a complete drum kit, a family of recorders and numerous other instruments including a Brazilian cavaquinho and rare Chinese pipa. A neat, slender man with bright eyes, a quick laugh and surprisingly modest hands, he wore comfortable, casual clothes and betrayed no affectations. He began the interview by popping into the room and saying, "Well, Howard, what do you want to know?" So I leapt:

HM: You played solo concerts in Germany in mid-October last year, having just released Testament, a three-cd set of solo piano concert music. Let's start there: Are solo concerts still challenging you?

KJ: Someone I was talking to said, "Those are hard things, right? Why are you doing them?" I said, "I don't understand the question." Yes, they're hard. I almost die sometimes, doing them. But why am I doing them? This is what I do. This is who I am.

It's a ritual that I sort of invented, and also a bio-feedback mechanism for me. I don't actually know how I'm doing sometimes until I hear what just came out from my hands, and then I realize I shouldn't stop. I'll stop as soon as something is not working right three times in a row -- I mean if I play three concerts and I'm not happy with the results of any of it. Then it's a trend. But that hasn't happened.

[As for Testament, the concert in] London takes two discs, Paris is one. It just worked out like that. I tried to figure out if it was possible to take a couple pieces out of London, but every time I take something out, even if I think it itself is not absolutely necessary, the flow changes. One thing people don't probably think about when they think about my work is how good I am at programming.

First of all there's no material for solo. Now that I start and stop [within a concert, rather than play one long improvisation] I program a new piece to follow each piece, and it's strange structurally to take any of them out, it just feels wrong. I have an intuition for that in the trio, too, because we never plan our sets at all. We don't know what we're going to play.

HM: Do you remember everything that you've played as you play?

KJ: No. Some part of me does though. I think on Radiance [recorded 2002, released 2005] I start a piece with two particular notes, then it goes through amazing transformations and ends on those same two notes, though I didn't remember that I started on them. Some part of me is keeping track of this in a nonlinear way.

HM: Obviously you work hard to be in the moment and not be beset by anything else.

KJ: Yeah. It's a problem for other people around me, but that's what I do [laughs].

HM: Your fans take their chances.

KJ: I don't mean them, I mean people actually around me. Like someone says to themselves, "Keith seems to have a rule, he wants to have not so many people at dinner before the concert, he wants to be quieter." But there's never a rule! They'll see me come in and say, "Who else can we have here for dinner?" It's true, if someone starts talking at dinner before the concert about domestic details, I'm out of there. Everybody's got a family, everybody's got stories they tell and forget where they are. But I can't forget because I'm the guy who does the programming. I can't forget that I'm the leader of a band or that I'm about to do a solo concert.

HM: You're focused on getting to the piano bench.

KJ: I can't listen to it. I like being distracted so I'm not thinking about going on, but if conversation deteriorates to garage doors or laundry detergent, I will probably not want to hear that before I invent a new piece of music.

HM: You're letting your unconscious do the work, you don't want it to be sullied by trivial stuff.

KJ: I don't mind joking around before going on. In fact it's very helpful, as in London. Did you read the liner notes for Testament?

HM: I did. They tell an intense story [of responding to emotional distress at the breakup of his marriage by quickly instigating solo concerts in Paris and London, recommitting himself to the solo art], and explain something about the intensity of the music, too.

KJ: That's true. And all the engagements I've played since then have been extraordinary. I just flew to Naples, did one concert, it was unbelievable, I flew back and now it's coming out [in 2010]. My projects have seemed to step up to a higher plateau, another level.

HM: I hear a different kind of complexity in what you play here, a sound you've described as not atonal but multi-tonal. It's in a different realm than much of what you've done.

KJ: When I played my Carnegie Hall concert, Michelle Makarski, who was the violinist on Bridge Of Light [1994], my pieces with orchestra, came backstage and said, "Oh, those interludes are so wonderful! Great idea!" I said, "What interludes?" She said, "Those atonal things that connect the pieces." I said, "Those are pieces, too, Michelle." If I could, I would continue longer with them. When I practice sometimes they go on for 40 minutes.

But you need an audience so focused that it's willing to get inside that language, because you're delivering them the language and they're not sure what they're hearing. If they were able to stay with it long enough I'd know it, I would be able to tell they're not itching in their seats. Or I would feel in the air that it was something to do. It depends on the piano and the hall, but is also a result of some things I realized when I was ill with chronic fatigue syndrome and also again when I was preparing for the Radiance concert. I realized I wasn't letting my left hand be free. It might play vamps or weird harmonic things but it wasn't an equal partner and I wanted to see if it could be. It's working more and more like that now, in different ways. Each concert has its own version of that.

HM: Your hands sounds like they're working together.

KJ: There's an interaction between them which is much more like dialog.

HM: This is also why I'm asking if you remember everything as you're playing. You are both a composer and an improviser, and the structural challenge of improvising that involves maintaining a unity --

KJ: Some sort of core to each piece, yeah. . .

HM: -- you are trying to forget about this, but --

KJ: I also want it. Yeah. What I've learned is that if you let your body do something instead of whatever part of your brain manages quality control -- "No, I don't like this sound, yes I do like this sound" -- you're better off. I believe bodies have knowledge. I know my left hand has way more knowledge than what I tell it to do. Like in Naples! Manfred Eicher [Jarrett’s advocate and record producer since Facing You (ECM, 1972) was here a couple Sundays ago. He hadn't been here for 30 some years. We were going over my possible future releases and I played Naples for him and he said, "You don't ever need a bass player, this is it. It doesn't matter how complex it is, there's always something happening, underlying this whole thing." And I wasn't playing bass lines, really. I'm just learning as I go. I'm still learning.

HM: You let yourself explore onstage.

KJ: That's all I'm doing. It's all exploring. I better not have a sound in my head when I walk onstage. If I do, I'm shooting myself in the foot, painting myself into a corner. There's only one exception to that which I remember being worth it. It's the very first thing I played in London.

Recently it seems I open my concerts with something abstract, because I don't want to play a sound I know. I want my hands to play something and I want to be surprised. The very first sound has to be surprising. Wherever that goes, I'm monitoring the situation but don't try to control it much. But in London there was this ridiculous message I was getting, "You have to do this thing in D flat, there has to be a D flat" -- D flat was the message. D flat major mixed with other kinds of arcane momentary sounds, sort of spacey, trippy but slow. That's all I knew. I walked onstage with that and I thought if I can't get it out of my head I'd better see what this message is about. It turned into one of the most interesting beginnings of a concert that I remember. If it was just for that and one or two other things from London I'd have to release it, even if everything else was cockeyed somehow.

These things turn into structures probably in the way when water freezes it turns into a shape. Except I'm not freezing onstage, I'm melting something, or molding something. It isn't cerebral. If you've heard it a couple times, you've heard things like very melodic things, where the melody never repeats but somehow you know where you are. It's a string of melody that goes on and reminds you of earlier parts of it yet never repeats specifically what I played before. And I like that. That's something I let happen. The idea of going back to A as in AABA, if that happens, like in the last thing I played in London, that rock piano sort of thing, it happens on its own. In London I didn't have the melody in my head, I didn't have the sudden change, it's all in G major then suddenly I go to F and then C and then G, and it gives you just enough of a color change to raise your eyebrows. The ending sounds like it must have been invented ahead of time, but it wasn't. That all happened by itself.

HM: Do you see different scales have different colors, different emotional attributes?

KJ: Yes, but I don't think any of them have those attributes all the time. I think it's a relative thing. A major is pretty happy, usually, but it depends on what you do with it. There are things that you can't get away with, get away from, like C minor's darkness. It's probably always going to be dark. But the multi-tonal word I use instead of atonal -- this is because I'm hearing tonality moving like at warp speed from one thing to another, but still hearing it as momentary tonality. When the combinations of notes are passing each other, it's like two cars on the road. You say, "I think I know who that was," and you're passing each other at 60 miles an hour, "Is that so-and-so?" That's the experience I want to have with tonality in some of those abstract things. It's an orchestral effect.

It's hard on a piano to be orchestral, but sometimes I try to be multi-rhythmic also, so there's no tempo but it's also not rubato. You would have heard that in some of Paris and London. But it's very hard to do. Because the pianist has two hands -- how many tempos can you suggest at the same time? It's a bitch. There are some parts of my Naples concert, when that comes out that, you'll hear that I managed somehow to be several players at the same time.

HM: Is this musical point you've arrived at something you dreamed of early in your career?

KJ: Is this an aspiration I had? A goal? Not until I was near a testing site for it. In other words, before the Radiance concert I had to be preparing for solo, and to do that I had to be in such good shape, and to be in that shape I have to be playing as though I'm playing a solo concert, and usually I learn something or see something I didn't yet do, which I see as short term goals. But I'm not thinking about them until I'm actually playing. And the music itself suggests to me there's more to do, each time.

When I was sick with chronic fatigue syndrome and was sure I would never play again, I decided if I got better I had to dedicate myself to being an improviser, because that's what I essentially am. There's an anecdote from my childhood that plays into this. When I was a teenager the youngest of my four brothers was living at home. He had been taken out of school because he didn't want to go to school, so he was living at home, stuck in the house with his grandmother most of the day. He was frustrated, of course. I'd visit once in a while. And a couple times he went to the piano, though he knew nothing about the instrument, didn't know a scale, and he'd start playing. And I'd say to myself, "I wonder if it's possible to do this if you know the instrument."

Because what's coming out was accidental, he didn't know he was doing it, and the moments it was really happening, he didn't know them either. But I'd been a pianist since I was three, I knew the piano and I wondered if it was possible to not throw away your knowledge of the instrument and still inhabit the zone where you could take it to that place. Because I was hearing this clash of sounds from him that to me was beautiful.

Beauty is so tremendously misunderstood. The universe isn't asking let planets be created without any explosions. [laughs], "We don't need explosions here, because everything is beautiful, and it's the hippie era," or whatever. I think, in the sense that you asked the question, my goal would have been to make my music more and more like the universe. There have to be clashes. There have to be times when there's almost nothing happening and you're almost bored. Or it's too long . . . or something. The reason I know this is right is if I try to take something away from a concert, I'm left feeling, "Wow, that really doesn't work. I would never have played that after that other thing." You take this little piece out and the whole universe sort of droops wherever that piece was in the concert.

HM: Could anybody else play your music?

KJ: You probably know the Koln Concert [1975] exists in sheet music, authenticated by me. I went through it with a fine tooth comb and the guy who did the transcription was really good, but I'd never do that again, and it was a way easier concert than what I'm recently doing. If someone tried to transcribe me now, they wouldn't be able to do it. Some things they could get, some things they never could. I think one of the things that's great is that it's unrepeatable. Even if I had the music and I decided I'd play it, it wouldn't be as good.

HM: Do you foresee a time you'll return to composing, to fix your ideas and work with them as you can only do in that form?

KJ: I don't know. I also write, I'm a writer, and I think I would turn to that somehow. I've been doing that all along. I recently got into it all over again. What I write now are these comedy miniatures, sometimes only one page long, sometimes quite long, and sometimes they're not just comic. Sort of satirical things, meant to be laughed at broadly by the reader, or read out loud. Writing's wonderful, it's like playing to me. I'm at a distance, watching this writing come up, thinking that it's funny or whatever it is I feel, but like it's coming from another place though I know my fingers are doing it.

HM: Do you ever try to make anybody laugh with your music?

KJ: At soundchecks with the trio we're always cracking each other up. But no, I don't try to crack people up at concerts. Sometimes there are these little perfect things that make you laugh, though. I've had several listeners have the same exact response at the end on the Naples concert -- I've seen them light up, go "Whew!" That happens. Sometimes funny and astonished can go along with each other, or curious or surprised.

HM: Are you surprised when you begin to play something that sounds really serious, significant and perhaps grandiose?

KJ: Maybe you're thinking of something I did in London, that went on for about ten minutes, has a motif that continues to stick around once it shows up and goes through metamorphosis. Yeah, that I love. And you ask was I surprised? Yeah, I'm surprised, when it somehow locks itself in, not as in a closet but locks itself into place, and no matter what I do it won't go away, it's what I'm dealing with. And the rest of what I'm playing can be completely crazy but this thing is still there, hiding, then back out front, and very often the challenge is "How far can I take this?"

HM: At what point do you, or maybe you never do, say "I am going to extend this. I am going to put my will into extending this"?

KJ: Oh, pretty early on. I mean, I have to do that fairly early on or it will be, "Excuse me folks, let me start over." Which I have done, but that's mostly because I'm playing a tune and my hands may be blasted away from the concert. Fairly early on I commit myself. It's like: "Are you committed. Are you doing this? Are we doing this?" I have to say yes or no.

HM: But you want your hands to be leading this, not your musical mind?

KJ: They're working together. I try to be a monitor and let it come down whatever way. That's why the two concerts from Paris and London are so different. They're only two or three days apart. You'd think that there would be similarities, and there are. But also what I've been saying for years about pianos make a difference, halls make a difference and the audience makes a difference shows up really clearly on these two concerts.

HM: What kinds of things are you looking forward to doing? You seem like someone who would be thinking of things you want to accomplish.

KJ: I feel the same that I've always felt. I trust something will come up.

As Keith Jarrett showed me his music room, we continued to converse. Here are several excerpts from our less focused talking.

HM: Your music is exactly the opposite of Philip Glass's.

KJ: I'm glad you said that.

HM: I was thinking about how you do and don't use repetition --

KJ: The minimalist thing . . .

HM: -- to the point where the music sounds completely different than what you first thought it was.

KJ: Yes, it's not minimalism. I don't have a word for it, but it's a certain kind of American energy manifest in a classical format, which is a piano onstage and soloist coming on, having no tricks, no magic tricks, just to sit at the piano and use the piano as a tool.

HM: The only classical pianist I think of getting to some similar musical territory is Scriabin.

KJ: Yes, Scriabin. There's also Ligeti, who did some of the music for 2001: A Space Odyssey [Stanley Kubrick's 1968 film). He wrote a bunch of sonatas, relatively unplayable. At least they look that way . . .

HM: How do people react to your music when it's not what they expect it to be?

KJ: I've actually had people come backstage -- not in recent days, but in recent years -- but I remember times when I was going through a certain thing onstage while I was playing, then people would come back and I'd ask them, thinking they'd be open about this, about what they were experiencing. I'd say, "Can I ask you a question? When I was doing this section" -- and it would be easy to describe somehow -- "tell me what you went through?" And they would describe something parallel to what was happening within me, and I wouldn't have told them a thing. This was not difficult, atonal or multi-tonal music, just something that was in a much different style that I used to have than I do now. But, what's interesting to me is that the listeners went through boredom exactly where I did, looking at their watches going wondering, "How long this will be going on?" Then a couple minutes later they'd be in it, and they couldn't actually say when that happened.

The same thing happens when I'm playing, if I start one of those abstract pieces I often say to myself what the hell am I doing, this is nothing, there's nothing happening, just a bunch of notes, and then I think, "Well, ok, I didn't find the place where these notes make sense yet. And that place isn't far away." I'm sure people might not like it, they might say, "It's not my favorite thing he does," and then -- "Oop, there's something there!" And they don't know quite what it is. I love that, that's the way it should be.

HM: We didn't even talk about your quartets -- music that people remember and love.

KJ: The American quartet [featuring saxophonist Redman, bassist Haden, drummer Paul Motian), that was like raw food all the time. There was an energy thing that happened with that band sometimes that was pretty incredible.

HM: You were really the magnet there, the center pulling things together.

KJ: Yeah, I wasn't exactly the pianist in a band. My favorite bands were bands without pianos. I liked Ornette [Coleman], I liked Gerry Mulligan's little big band, I tended not to like piano-infested music that much. So between the fact that Dewey didn't like to play on chords, and I liked to play little percussion instruments, and bow out for long sections . . . Well, you could say I put it together.

I remember this one time we rehearsed and Dewey was a slow reader, he couldn't play this piece that was supposed to be fast. And he was two hours late for rehearsal, anyway, we'd been waiting, waiting, waiting for him. Finally Dewey showed up, but couldn't play the song anything but very slow, so I said, "Ok. Charlie [Haden], you'll hear where Dewey is with this, and Paul [Motian], you play as though it's fast." So yeah, I was the musical director of a band that would have never organized itself. Dewey and Charlie had played together but Paul probably never played with Charlie, and I don't think Dewey had ever played with Paul.

HM: Were you musical director with Charles Lloyd, also?

KJ: No, unless it was by default. I did write arrangements for a big band once that Charles was supposed to have written. Do you know my piece we did, "Is It Really The Same?" which we played in Russia (hums the theme)"?

The trio [with Gary Peacock, bass and Jack DeJohnette, drums] plays it now. It's like old, old wine. I remember where I wrote it, in Sweden at this lady's house where she always cooked spaghetti for all the jazz players. I hadn't played it in years, but I remembered it existing, and now we play it again. That doesn't happen often, but it does happen.

HM: Do you like traveling everywhere, or are they places you prefer not to go?

KJ: Certain cultures either help me or don't. I like playing in New York for example. New York has its own feeling. There's a New York audience and then there are all the other audiences, none of them like New York's.

There are other places I enjoy visiting. In general for me it helps if the places have a certain passionate tradition, or people are passionately engaged in something going on. When I was in Naples, our tour assistant was a young woman from Eritrea who had been raised in Naples, and at this moment we were there a lot of people were fleeing Africa to get to Italy, and they were even being followed by government officials from Eritrea, and there were Italian government officials who are helping to find them, to send them back so they go to jail or be killed or whatever, I was with someone who is from this thing, having this conversation about artists in Africa and artists elsewhere . . .

HM: The passion of these places means something to you?

KJ: It helps. In Naples I ended up playing on the frame inside the piano in a way I hadn't in so many years, because I was aware of Africa in a way that I am not always -- yet I was in Italy. I felt I was walking a tightrope between all the cultures I'm aware of, all the listening I've done. I don't have material, and what comes out it not of Italy, it's not of where I'm playing, it's coming from inside myself and it doesn't belong even to me, it just goes into the air and vanishes. These kinds of conversations there geared me into a sort of new realm.

HM: Do you seek out travel to places you haven't been for that reason?

KJ: No, I actually like going back to places I know. Halls, you never know how the halls are unless you've been there. If they're good, you don't mind going back.

HM: Have you been to Brazil or Argentina?

KJ: Yes, I had similar kinds of experiences in South America. One guy came backstage and said, "I know what you've been listening to. There's a Brazilian dance, but how did you hear so much of it that you know?" I said, "I don't know what you're talking about." He said, "Well, you're playing it!" I said, "I understand that, that could happen, but I've never heard it." In Japan, people will say to me, "That sounds so Japanese." I'll realize, "Oh, I'm doing something with a pentatonic scale, and I'm playing this in Japan and so it sounds Japanese."

But often I don't play the piano as though I'm a pianist. I try to play it as though I'm many types of instruments. Very often I play as if I'm a voice. The piano works on a lever system, you know, and when those levers are there, they're just hitting something. The freeness you have to play a horn or to sing isn't there. It's intractable; there's nothing you can change about the instrument's way of delivering the sound.

But I would guess I'll go down in history as someone who coaxed out of the instrument things that were not pianistic, and people will wonder, "How did he do it?" There's one track from the Paris concert that sounds like Italian to me. I didn't remember thinking that while I was playing it, but it's a piece in which I'm playing tremolos, and it is operatic, the tremolos could be guitars . . .

HM: You get bell-like things out of the upper register, too.

KJ: Yes, it's never a piano to me. It's always a tool I use that happens to sound like a piano when everything's average. An average player, it will sound like a piano. Steve and Alain, our soundmen, go around every time I'm about to do a concert, they try to get the sound that I get just with one note, or a chord. And every time they say, "This is not possible, Keith." And yet it is a lever system, that's all. So there is magic in there. I think the will has to be so strong to push it out of its comfort zone. I go out of my comfort zone, and the piano has to follow.

HM: When did you develop that kind of relationship with the piano?

KJ: That probably would have been after [I attended] Berklee. And probably after a very intelligent bass player I had said one day, "Why do you play so clean? Do you want to play that clean?" I said, "I don't! No!" Since that moment, I have tried to probably force issues on the instrument. To say to myself, "See if you can do this."

There are different techniques you can be taught in the classical world, such as the Russian technique where you hold your finger on the key and the hammer comes down slightly and it moves up and down just slightly. I'm sure I'm doing that, but I'm doing a bunch of things with overtones also, as a good listener can hear. On the first track of the second half of the London concert, on the second London cd, the very first thing is a vamp in G minor and I managed to have the piano speak to me in this particular way with this one B-flat. Sometimes one note in a concert is enough for me to have made it worthwhile to play.

One night Gary [Peacock, bassist] was in a funny mood, he might have had a lot of espresso, we were about to go on and he said to me something he never says: "Let's knock them dead." He tells his students this story. He says, "And Keith looked me right in the eye and said, 'I just want to play two good notes.'" That's it! When those notes are intentional, you've been rewarded. If your intent was manifest in the air, and then even one person notices it!

Another thing Gary said -- in a BBC program about me they asked him, "You worked with Bill Evans and Keith -- what's the different between their touches?" Gary sat a minute and said, "Keith has a sound. Bill had a sound that depended on his touch, his one touch. There's something kaleidoscopic about Keith's sound. You can't tell what he'll do, but it's all about touch." I'd never know what Gary thought about this, but it was a great answer. I had always thought of touch as a way to change.

In 2010, I spoke again to Keith Jarrett by phone regarding Jasmine, a just-released album of duets from 2007 with bassist Charlie Haden. These are notes, not an precise transcript.

HM: There's a buzz going around about this album.

KJ: I’m experiencing karmic actuality right now. An obsession with my work. It's nothing new, and won't go away, and I don't want it to go away. It tests other people to figure that out. People see it on stage. “God, he should be in the marines, he lives a very disciplined life,” they think.

In 2007 [when Jasmine was recorded] I think my life was in upheaval but I didn't know it. It wasn't anything I'd connect with the music -- in the end, over the three years since then, I more and more saw the recording as a ballad release, and it was great to be able to do that, who did that since Coltrane?

With a duo you can do way less with tempos than with a drummer — I mean, fast tempos. It’s not boring, working with Charlie. Together we pared [the material we’d recorded] down. I was taking charge the first year and a half; Charlie just wanted it out there. Then I think he realized Manfred does these things methodically, and I trust him. So then he [Charlie] became a great ally working on this. I don't think I'll ever have another better partner in choosing tracks. Usually a jazz player will say I didn't like how I played on this one. When there are only two of us, it' even harder -- for Charlie, for me -- but in the end we chose what music kept its integrity throughout the entire track. Throughout this virtuoso concept, the solo concept became secondary.

HM: I heard it related to The Melody at Night with You [Jarrett’s solo album recorded 1998, following his struggle with chronic fatigue syndrome].

KJ: What I tried to do, as I tried to do when I had the American and Swedish/Norweigan band [with saxophonist Jan Gabarek, Palle Danielsson, Jon Christensen] I never mixed what the two band were playing. With the exception of a couple tunes here with Charlie, these were things either I thought of for this project -- “One Day I'll fly Away” was a song I think written for Moulin Rouge, [Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 film], Nicole Kidman sings it, when I heard it I thought I liked the song -- but I waited for Charlie, to rewrite it. In the movie there’s a giant orchestra behind her, and a lot of transitional material from one part of her singing to another, she's looking around -- I had to take out chunks and add a way of looping this thing somehow, so it would work with a chamber music concept. That was essentially driven by the fact that I was going to play with Charlie and I could hear his intonation. It's in B major, a rare key. The one [track] with all interesting contexts is “Don't Ever Leave Me” -- one of my favorite ballads, and it does have relation to my life. The way Charlie plays on that track made that version absolutely unlike anything else that could happen. Charlie has a way of swaying, you could dance to that -- in your living room -- because of his sound, his swing, his intonation.

An incredible amount of work went into the sequencing of this record. But the way it came out is completely irrational. The first two tracks are almost the same tempo, almost the same length; then the next two --there are three pairs, the nine-minute pairing, the short ones in the middle, then the two longer tracks side by side -- that was not intentional -- then a medium to long version of “Goodbye,” and the very short piece. If I were a mathematician, I’d say this doesn’t add up.

There was the problem of things not being in the same key two times in a row. I was following the typical restrictions I always make, but it popped up -- there was no way to get better. That first E flat chord, the B flat pickup, then we come in at the same time — that's the beginning of something, it had to be first. But deciding that was like going nuts for three years and then going very sane.

If you take the entire working lifetime in the pubic eye of both those bass players, Gary and Charlie, that demonstrates both their differences and similarities. They have basically lasted a helluva long time. They haven't had the same kind of musical listening education; they're different in that sense. Charlie listens to singers and so do I. He's very aware of the lyrics of these things -- which is a reason ballads would be good for both of us, we know what they're about. Whereas Gary was very unaware of the lyrics. A couple years ago he asked me, “Keith, do you know the lyrics to all these ballads?” He figured out that was how could I be phrasing this way.

If you know the thrust of the message of the piece, it really helps. At one point I was thinking of releasing the lyrics to each song, even though it's an instrument album. Then listeners would go to analyzing [the instrumental interpretation], and look for the song on vocal albums. It probably would have been the first time on an instrumental album that the lyrics were include.

Gary and I have never played duos. I don't think I would have noticed that element of Charlie's if we'd had a drummer. While we were playing, Charlie looked at me and said, "Keith, I had no idea you have such good time. I don't remember that about you.”

I said, “Charlie, you and I have impeccable time.” It's easier to know that about a bass player than a pianist, because a pianist can phrase outside the rhythm and made it work. But pay attention to the beat of the ballads, and how often, even during the double time parts of them, we always know where one is, no matter what we're doing, but come together almost as if someone's conducting it.

Gary's contribution to music has been very technical. He raised the bar [for bass playin] back in the '60s, he and Scott [LaFaro]: Gary with passion and taking risks, Scott getting everything he tried for, and practicing all the time -- which I appreciate. That's what jazz is all about

I'd say Charlie has developed the center, the core, from the listeners' point of view. If he's not given chords, he stil knows how to move along with the soloists. They're so different, he and Gary . . .

We recorded as a duet before, yeah -- on Charlie 's album Closeness [1976]. But that wasn't even the tip of the iceberg. He’s on the BBC film with me, The Art of Improvisation. I called him a week after to record Jasmine. I said said we've got to do this -- I'll pay your way to the East Coast, with your wife, bring your bass, we'll record, and we’ll be sure not to release it until every track gets a committed “YES, two thumbs up,” from both of us. By the end there no disagreement on any track. That doesn't happen, really. Even with Charlie back in the quartet days, when you've got two guys in the mixing room deciding whether you need to take another track -- if Charlie doesn't like his playing, or I don't like my solo, the tradition is to say, “Let's do another take.” This session was purer than that. We spent nighttime after nighttime listening to these tapes. I never got tired of them. I'm sure I listened to them hundreds of times.

I had to play to the dynamics presented, because with a drummer that's a whole different set of dynamics. Usually I'm the one hard to hear -- when Paul Motian played with the quartet, I was always playing rather loud. In this case, I used the soft pedal a lot. I had to play down to Charlie, while Charlie was trying to blend his dynamics and luckily we had the engineer I like from Switzerland to do this. My studio is not meant for this kind of recording. It’s too small.

I had agreed to meet with Charlie for the film they were making on him [Rambling Boy by Reto Caduff] I told him I'd talk, not play. They weren't prepared for it, when we did play a little. But that's what made me realize there is so much potential here. And so we recorded it, in April three years ago.

We were having enough fun playing it didn't matter what the camera people were doing. And I hadn't played with Cbarlie or thought about playing with him for 33 years. You know, Charlie wasn't clean most of the time I had him in my quartet. This was the first time we worked together when he was cool, when everything was alright for him. It made a big difference.

What I get from Charlie is all the depth without heaviness -- that's the sound of his bass. That's why I use the engineer I do, why I like Martin. I thought this would be something that could not vaguely come out, due to sound issues -- but he took the problematic things about the piano, used the things good about it somehow, brought them out slightly, without changing anything -- adding just a tiny tiny tiny bit of echo. He started with more, but Charlie and I wanted to hear what we heard when we played. It was such a relief. You know why you played a phrase with a certain dynamic -- you can hear the room, you know why you did it -- but when it’s messed with, you lose reality. You think, “Why would I play that loud there?” or that soft?

Charlie’s virtue is his listening while he plays. I wouldn't call him a technician but he's so good at what he does he has to be a technician. Gary almost never has an attitude about whether one thing is better or another is better. He just goes for it. They’re really different players. I'm glad to have played with both of them. Gary's a hero for me, he's gone through so much physical craziness. He’s almost a decade older than me. Charlie doesn't have the kind of trouble that Gary has. Gary can't even hear his own playing now. Can't tell if he's in tune sometimes. How heroic can it be, to be out there knowing that and going for it anyway? He's been pushing the envelope for so long. He was in my trio trio in 1964 and again in 2004 --

There’s no way to compare certain things, they’re apples and oranges. Charlies' taken a lot of different directions at the same time. In that sense he and I are reasonably alike. I mean I’ve been involved doing the classical things, off-the-wall organ programs, playing the clavichord. Meanwhile Charlie's doing his Liberation Music Orchestra, Quartet West, country influenced recordings and Latin stuff.

We came to record Jasmine with the same intention. We knew what we felt on the BBC film, we didn't want to mess with that. I don't like it to mess with purity when it's there already. I was not going to say “Let's play free,” or something like that. I don't really like duos. I don't like chamber music in general -- I had to find my way into this in such a way that it's not really chamber music. It's got everything jazz has, but the essence of it.

You can't do that with drummers, really. Drummers are drummers, they hit things. Gary said that at lunch one time, on tour, over a coffee. He was just thinking about drummers, and said, “They hit things, that's what they do, they hit things.” In essence, that’s true. So what I think we did with the duo thing is we managed to make a statement that really isn't about how to play without a drummer, it's how to play music as though there are no drummers. It would have to take two people who have incredible time, not rely on somebody making cymbal sounds. So we were both patient. We kept this recording a secret for the whole time, then finally got to the pont where we knew exactly what should come out.

Manfred and Charlie and I had arguments about the takes. That was okay: We'd listen and investigate some more. I'd say we're talking about the overall feeling of the track, not one moment of the track, but the overall integrity. Does it actually speak with continual integrity? In the end everybody agreed with everybody. Luckily, the takes turned out to be the ones I chose. I'm good at that.

People have no idea what I put into every release. They really don't.

Howard, this 2009 conversation is maybe the most insightful Jarrett interview I've ever read. So much there, and I know I'll be returning to it. Thank you for sharing!

Great interview. I saw him in Toronto in 2014. “Pt. 1” made it onto his album. I tell you because it is a big deal for me and I don’t know anyone who cares.