Since 2001, the Jazz Journalists Association (over which I preside) has celebrated some 350 “activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz,” as Jazz Heroes. The class of 2024 Jazz Heroes has just been announced, recognizing the good works of 33

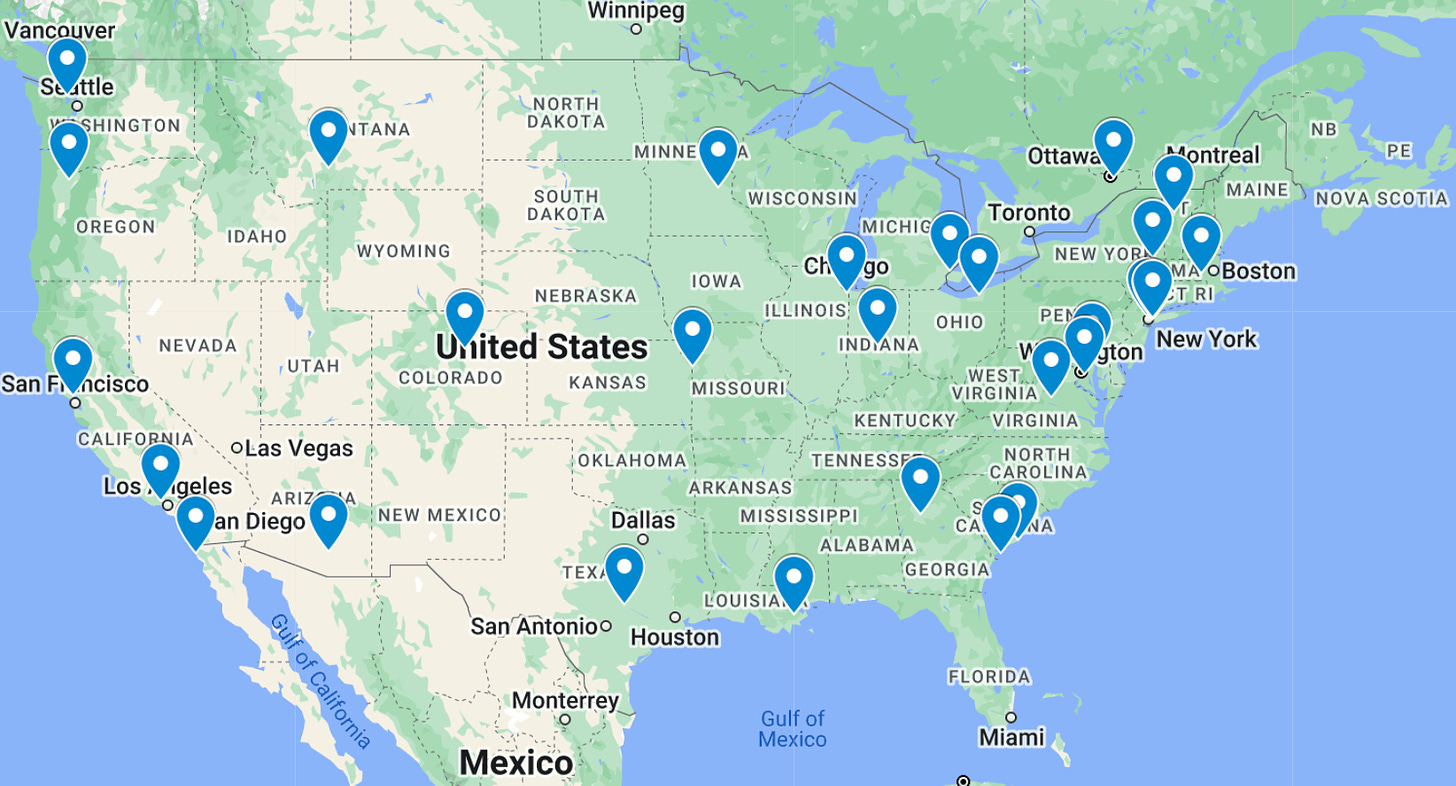

people whose efforts extend from the Baja-San Diego borderland to Ottawa, Canada, through 27 U.S cities, from Akron to Tucson, rural Montana to the South Carolina Lowcountry, New York’s Capital Region as well as Brooklyn and Harlem, Newark, Chicago, the Bay Area, LA, NOLA, DC, Austin, Denver, Boston, Detroit, Indianapolis, Charlotte, Brattleboro, Hilton Head Island, Portland, Seattle — where there’s music, there’s jazz (and given organizational resources, the JJA could celebrate 33 more . . .)

Jazz Heroes do the background work, sometimes acknowledged but seldom fairly compensated, that sustains as a vital cultural entity the past and present of an art form that reflects better than any other (I’ll argue) what people not much driven by commercial concerns do to keep themselves and their communities humming. Most serious jazz fans understand their connections to this music as more than a hobby, perhaps as much as a calling. It might be considered a lifestyle, or even a way of life.

Why these folks and and others (like me) love jazz more than (if not always instead of or to the exclusion of) other genres of music is a question for speculation, to what ends I’m not sure. I grew up on Chicago’s south side in the ‘50s, jazz was in the air but so was Sinatra, Elvis, show tunes, r&b, popular classical works, Lawrence Welk, tv and ad ditties, quasi-Jewish music and movie soundtracks. I’m temperamentally partial to narrative drama, heightened emotions, saturated colors, sudden (spontaneous? unpredictable?) action, an ethos that values imaginative engagement, emotional range and a whatever’s-necessary work ethic. Demographics + personal preferences = personal esthetics. Call that news? Seems tautological.

But what’s cool, maybe deserving of note, and demonstrated clearly by the JJA’s Jazz Heroes campaign is that this music, for many years reportedly representing a tiny and diminishing percentage of record sale and concert returns, holds sway beyond such metrics. Jazz may be deemed elitist or crass, the most elevated form of spontaneous creation or sheer noise, but it’s here, everywhere, ineradicable. Its proponents are working across many sectors of the arts world, from artist to audience, patron to promoter to presenter. Think too of the references to jazz — the sound, the iconography, the immortals — that pops up in advertising. See what jazz is used to sell, then consider how jazz-the-music may not be selling, but jazz-the-idea is.

[Yet — maybe that’s not quite true. André 3000 playing processed flutes is fine by me.

In the last week thanks to Ashley Kahn’s DownBeat Blindfold Test of Cecile McLorin Salvant, I learned of Laufey. '“She’s the most famous jazz singer today,” said the most

radically gifted jazz singer to emerge in the past 15 years (talk about this elsewhere). I get it. Doesn’t everyone dig bossa nova? Isn’t kind of brave of this Icelandic-Chinese woman who turns 25 on April 23 to play guitar and piano and sing solo front a string ensemble, drawing uninitiated listeners into the pleasures of soft swing. To the extent that she’s successful, maybe it’s heroic? Or is Laufey just codger-bait?]

Stardom is not requisite for JJA Jazz Heroes. Some have been brushed with fame: Marla Gibbs, for instance, who turned her earnings from high visibility tv roles into support of the Black arts and music movement of Los Angeles; Ahmed Abdullah, trumpeter traveling the spaceways with Sun Ra for decades, and co-directing the Brooklyn cultural center Sista’s Place; Charlton Singleton and Quentin Baxter of Grammy-winning Ranky Tanky, preserving by updating the Gullah traditions of the South Carolina Lowcountry. But others shine in relative isolation: Pianist Ann Tappan, who teaches from her home in Manhattan, Montana, a town of 2000, outside Bozeman; David Leander Williams, who became historian of Indianapolis’ Indiana Avenue, since no one else had; Arthur Vint, who’s established a cool club in Tucson, having learned how laboring in that temple of jazz, NYC’s Village Vanguard; trumpeter-composer-bandleader Iván Trujillo, who crosses the Mexico-U.S. border and jazz sub-genre lines, too, bringing traditional New Orleans jazz, free improvisation, electro-acoustic and classical music to binational Baja California-San Diego, recording with young players remotely during the pandemic, as below:

I’m proud the JJA shines light on everyday heroes, who make the world go ‘round.